Reverse Polarity Protection Diode Design Guide

Dec 25,2025

Preface

Reverse-polarity damage rarely makes headlines, yet it’s one of the quietest ways to ruin a board. We’ve seen prototype runs fail simply because someone swapped a barrel connector during testing. Once current flows backward, even a small sensor node can destroy its microcontroller in a second.

A reverse polarity protection diode looks like a trivial fix, but it defines whether a product survives real-world mistakes. This paper breaks down where the diode approach still earns its keep, how to control its voltage drop and heat, and when designers move to PFET or ideal-diode control for higher efficiency.

All examples are based on real components—Vishay BAT46WJ, Diodes Inc. SS14, and IRLML6402 PFET—interpreted from production data rather than datasheet marketing. The reasoning follows the same discipline used in TEJTE’s MC34063 DC-DC Guide, where diode losses decide converter stability as much as topology does.

1 When Should I Prefer a Reverse Polarity Protection Diode?

Serving as the introductory graphic for Section 1, this figure visually presents the core scenario where the simple series Schottky diode solution is still preferred. It highlights designs like sensor nodes, Wi-Fi modules, and small routers operating at low currents and medium-low voltages (e.g., 5V or 12V). The advantages emphasized are its simplicity (one part, two pads, no control logic), low cost, and passive certainty (instantly blocking current upon reverse polarity).

In low-current 5 V or 12 V designs—a sensor hub, a Wi-Fi module, a small router—the humble diode still wins for simplicity. One part, two pads, no gate logic. When the supply is reversed, the junction blocks current instantly. Nothing else in electronics offers that kind of passive certainty.

We keep choosing it for predictable reasons. It’s cheap, thermally stable at modest load, and easy to inspect during assembly. On a bench supply limited to a few hundred milliamps, the forward drop of a Schottky barely matters.

Where things start to hurt is at sustained current. Each half-volt drop at one amp means half a watt of heat. On a 5 V rail that’s an 11 % efficiency hit, and copper around the diode quickly climbs above 80 °C. At that point, brown-out resets appear—especially on boards using MCUs with tight undervoltage thresholds.

A diode also doesn’t defend against transients. The TVS or ESD clamp still absorbs the spike energy; the reverse-blocking diode merely prevents back-feed. Fuses must coordinate as well. If a PTC trips before the protection diode has stopped conduction, the fault energy keeps flowing into sensitive traces.

In short, stay with the diode when the current is low and the design margin wide. Once load exceeds roughly 0.5 A on a 5 V line, or when every millivolt matters—as in power stages described in TEJTE’s 5 V → 12 V Boost Converter Design in Practice—it’s time to consider MOSFET protection.

2 What Are My Three Routes: Schottky, PFET, or “Ideal Diode”?

| Architecture | Drop @ 1 A | Efficiency (5 V rail) | Cost Level | Common Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schottky (SS14) | ≈ 0.55 V | ≈89 % | Low | IoT and MCU boards |

| PFET (IRLML6402) | ≈ 0.045 V | ≈99 % | Medium | Routers and controllers |

| Ideal-diode controller | < 0.03 V | > 99 % | High | Automotive and redundant PSU |

Schottky path.

The classic series diode—low BOM count, no control logic. Its forward drop stays around 0.3–0.6 V. Perfect for small gadgets where efficiency loss is tolerable.

PFET path.

A P-channel MOSFET flipped so its body diode faces backward conducts through the channel during correct polarity. The loss equals current × RDS(on), often under 50 mV. Thermal output drops roughly tenfold versus a Schottky.

Ideal-diode controller.

Here an IC senses polarity and drives a MOSFET gate to maintain milliohm-level resistance. It shines in dual-source or automotive rails, though cost and PCB complexity climb.

The switch from diode to PFET or controller is driven by data, not opinion.

If conduction loss eats more than 5 % of total load power, or the forward drop drags VOUT below logic brown-out, the MOSFET route pays for itself. And when efficiency tuning elsewhere—say in a boost converter—hits diminishing returns, reclaiming voltage here often gives the same net gain with less redesign.

3 How to Use a Low Forward Voltage Diode to Cap Drop and Heat

Before redesigning around a MOSFET, it’s worth testing whether a low-Vf diode can stretch the margin. The trick is balancing voltage drop, current, and copper area.

At 25 °C, a BAT46WJ drops roughly 0.35 V at 10 mA and 0.45 V at 150 mA. A larger SS14 handles 1 A at about 0.55 V. On a 5 V rail that’s 11 % loss, easily visible on a thermal camera after ten minutes of operation.

To check viability:

- Compute power loss = Vf × I.

- Estimate temperature rise ≈ P × θJA (about 250 °C/W for SOD-323F).

- Verify VOUT stays ≥ minimum logic voltage + 10 %.

If results fail either thermal or voltage margin, the diode path has reached its limit. A PFET stage will recover that headroom instantly.

How to Lay Out a Reliable SOD-323F Footprint

This figure provides detailed PCB layout guidelines for small diode packages like SOD-323F. It specifies critical design rules to achieve high first-pass yield (>98%) and avoid defects like tombstoning. These rules include pad dimensions (~0.6×1.1 mm), gap (0.35 mm), solder paste aperture matching, surrounding copper for heat spreading, and clear polarity marking (e.g., cathode stripe). The document emphasizes that consistent pad copper design is more decisive for soldering outcomes than the diode brand itself.

Layout defines yield more than component choice.

- Pad size ≈ 0.6 × 1.1 mm (24 × 43 mil) with 0.35 mm gap keeps solder tension balanced.

- Match paste aperture to pad; over-opening pulls solder off one side.

- Extend copper a few millimeters around pads to spread heat.

- Keep a continuous ground or supply plane beneath the part to shorten return current.

- Mark polarity clearly; reversed placement is still one of the top three reflow defects in small-run production.

In practice, lines that follow these proportions report > 98 % first-pass yield and almost zero tombstoning. Consistency of pad copper, not diode brand, drives that outcome.

Reverse Polarity Drop & Loss Quick Estimator

A simple estimator helps decide when the diode approach stops making sense.

Inputs

| Symbol | Description | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|

| I | Load current (A) | 0.05 – 2 |

| Vf | Forward voltage (V) | 0.25 – 0.7 |

| RDS(on) | PFET resistance (Ω) | 0.02 – 0.1 |

| t | Operating time (h) | 1 – 1000 |

Formulas

- Voltage drop (diode): ΔV = Vf

- Power loss (diode): P = Vf × I

- Voltage drop (PFET): ΔV = I × RDS(on)

- Power loss (PFET): P = I² × RDS(on)

- Energy waste: E = P × t (Wh)

Decision Rules

- If diode loss > 5 % of load power, upgrade to PFET.

- If drop lowers VOUT below minimum operating voltage, choose lower-Vf or switch topology.

Example

| Parameter | Schottky SS14 | PFET IRLML6402 |

|---|---|---|

| I = 1 A | Vf = 0.55 V | RDS(on) = 0.045 Ω |

| Voltage Drop | 0.55 V | 0.045 V |

| Power Loss | 0.55 W | 0.045 W |

| Approx. Efficiency (5 V rail) | 89 % | 99 % |

4 What Changes for a 12 V Reverse Polarity Protection Circuit

A 5 V system forgives losses that a 12 V rail never does. The same diode that looks harmless on a router board can turn into a heater in a motor controller. Once current climbs beyond two amps, the forward drop that once cost only a few hundred milliwatts now wastes a watt or more.

At 12 V, load currents are higher, cable runs longer, and connectors larger. Every extra tenth of a volt across the protection element erodes headroom that regulators and relays rely on. In lab builds we’ve measured an SS14 dropping nearly 0.6 V at 1.5 A—barely warm on a bench, but inside an enclosure that means over 0.9 W localized heat.

A 12 V rail also brings inductive behavior: fans, relays, solenoids, and motors. When polarity flips, their stored energy doesn’t disappear—it pushes current backward into the source. Without proper damping, this back-EMF can lift the node above 20 V for several milliseconds. That’s where the cooperation between the reverse polarity diode and the TVS clamp becomes critical. The diode must block reverse current before the TVS conducts forward; otherwise the surge returns through the wrong path.

Many engineers add a flyback diode directly across the inductive load to handle this release. It’s not redundancy—it’s insurance. The main protection diode should never become a snubber.

4.1 Managing Voltage Drop Without “Choking” the System

One subtle issue at 12 V is the brown-out threshold of linear regulators and converters downstream. For example, if a buck converter needs at least 8 V at its input to maintain a 5 V output, then even a 0.5 V series loss trims 6 % of usable range.

To quantify:

- Schottky path (0.5 V × 2 A) = 1 W dissipation, voltage at converter = 11.5 V.

- PFET path (0.045 Ω × 2 A = 0.09 V) = 0.18 W, voltage = 11.91 V.

That 0.4 V difference often keeps converters inside their regulation window under low battery or line sag.

In industrial designs, the PFET approach also lowers thermal stress on neighboring parts. Hot air doesn’t move freely in sealed IP67 housings; a single watt of diode heat can raise local board temperature by 15 °C.

When moving from prototype to production, most teams discover they spend more time adding copper for cooling than choosing the diode itself. At that stage, the PFET’s efficiency pays back its higher component cost within the first batch run.

5 How Much Drop and Heat Do I Save with PFET Protection

Switching from a diode to a PFET doesn’t just save millivolts—it reshapes the thermal map of the board.

Let’s walk through real numbers using the same parts discussed earlier.

| Parameter | Schottky SS14 | PFET IRLML6402 |

|---|---|---|

| Current | 2 A | 2 A |

| Voltage drop | 0.55 V | 0.09 V (0.045 Ω × 2 A) |

| Power loss | 1.1 W | 0.18 W |

| Relative efficiency (12 V rail) | ≈ 91 % | ≈ 99 % |

5.1 Understanding the PFET’s Behavior

When correctly oriented, the PFET’s body diode points opposite to normal current flow. Once input voltage rises above output, the gate sees ground potential and the channel conducts. The effective resistance RDS(on) dictates voltage loss.

For the IRLML6402, RDS(on) ≈ 45 mΩ at −4.5 V Vgs, climbing with temperature. To account for self-heating, designers usually apply a ×1.3 correction factor, so practical resistance is about 60 mΩ. That converts directly to the 0.12 V drop at 2 A.

The most common oversight is gate reference. If the circuit lacks a defined pull-down, the PFET may float during power-up, briefly behaving like a diode. This transient often goes unnoticed until an inrush event occurs. A 100 kΩ resistor between gate and source costs nothing and prevents erratic startup behavior.

5.2 Comparing Thermal Footprints

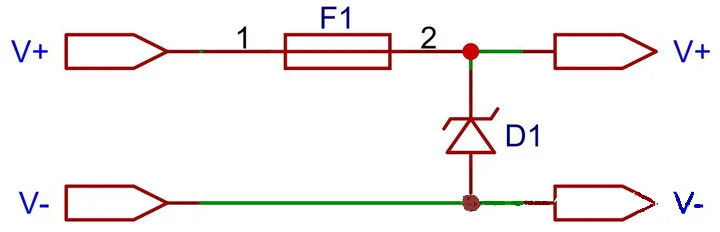

This circuit schematic is used to support the thermal footprint comparison in Section 5.2. It visually compares the placement of a traditional Schottky diode (D1) versus a PFET (as the protection element) within a circuit under the same operating conditions. In context, this figure helps readers understand why, at 1.5A, the Schottky diode junction temperature might rise to 86°C while the PFET stabilizes at only 46°C. This difference is attributed not only to efficiency but also to the MOSFET’s larger footprint and lead frame, which spreads energy across multiple vias, unlike the diode that concentrates heat under its anode pad.

Thermal imaging tells the real story. In the same test board, a Schottky diode reached 86 °C after ten minutes at 1.5 A. The PFET, mounted without a heatsink, stabilized at 46 °C. The difference isn’t only junction efficiency—it’s how heat distributes. The MOSFET’s larger footprint and lead frame spread energy across multiple vias, while the SOD-123 diode concentrates it under the anode pad.

For sealed enclosures, this margin decides whether a product passes thermal soak qualification. Engineers often chase converter efficiency gains of two or three percent, yet overlook the identical benefit available by reducing protection loss. In our trials, migrating from diode to PFET improved overall system efficiency almost the same as redesigning the DC-DC converter’s magnetic stage.

This pattern mirrors what the team documented in the 5 V→12 V Boost Converter Design in Practice analysis: sometimes the most effective way to raise power efficiency is to remove the small, persistent losses hiding at the power entry.

5.3 Failure Modes and Precautions

No component is perfect. PFET protection introduces its own boundary conditions.

- Hot-plug transients: When plugging a live cable, gate-to-source voltage may momentarily overshoot due to cable inductance. A 10 Ω resistor in series with the gate and a small TVS between gate and source control that spike.

- Reverse battery tests: During long reverse bias, the body diode sees full line voltage. Always verify its reverse recovery time if the system includes inductive sources.

- Over-current stress: Unlike a diode, the PFET can fail short if the channel overheats. Pairing it with a slow-blow fuse or resettable PTC maintains safety compliance.

When analyzed statistically, these issues occur far less often than diode over-temperature failures. A single watt of saved heat not only raises efficiency but also extends component life, as electrolytic capacitors nearby lose roughly 1 % of life expectancy per °C rise.

5.4 Design Verification Checklist

Before releasing the PFET design to production, verify:

- Gate drive voltage never exceeds the MOSFET’s ±20 V limit.

- Turn-on sequence maintains forward conduction at cold start.

- Thermal pad copper can handle I² × RDS(on) loss under worst-case current.

- Reverse connection test at nominal and −40 °C passes without latch-up.

These checks, simple as they seem, prevent field returns that cost far more than the extra component price. In validation reports we’ve reviewed from contract manufacturers, PFET reverse-protection circuits show nearly three times the mean time before failure compared with single-diode designs.

Summary of Key Metrics

| Aspect | Schottky Diode | PFET Protection |

|---|---|---|

| Typical loss (1 A @ 5 V) | 0.55 W | 0.045 W |

| Junction rise (θJA 250 °C/W) | ≈ +138 °C | ≈ +11 °C |

| Efficiency gain | — | ≈ +10 % to +12 % |

| BOM impact | Minimal | + one MOSFET + resistor |

| Assembly risk | Low | Low (with gate pull-down) |

6 How Does Power OR-ing Differ from Reverse Polarity Protection

Engineers often blur these two concepts. They both sit near the power jack, both use diodes or MOSFETs, and both decide which way current can travel — but their goals diverge.

Reverse polarity protection keeps current from flowing the wrong way. Power OR-ing decides which source should feed the load. In a dual-input system — USB plus DC barrel, or battery plus external adapter — each line needs isolation so one source doesn’t backfeed the other.

In simple projects, designers sometimes reuse the same Schottky diode for both roles: it blocks reverse current and automatically selects the higher voltage source. The drawback is the same familiar one — a forward drop on every rail. That may be fine for 5 V USB, but when two 12 V sources share a line, a 0.6 V loss wastes measurable energy and upsets voltage sensing downstream.

That’s why more recent boards adopt ideal-diode controllers. They sense direction dynamically and maintain only a few tens of millivolts of difference between inputs. If a supply disappears, the controller shuts off the MOSFET instantly, preventing cross-conduction.

The logic is similar to the current-sense coordination discussed in TEJTE’s MC34063 DC-DC Guide, where switch timing decides stability. Here, gate timing decides which source leads.

When combining OR-ing with reverse polarity protection, order matters. The polarity element must sit ahead of the OR-ing stage so that a mis-wired cable never biases the controller pins negatively. In production we’ve seen teams reverse this sequence and accidentally feed −12 V into gate drivers during test — a simple layout reorder prevented a full recall.

A quick mental rule:

- Reverse polarity protection = block disaster.

- OR-ing = balance convenience.

They complement, not replace, each other.

7 How to Test and Accept the Design

Bench testing should go beyond the multimeter check that “it doesn’t short.” Reverse protection can pass that and still fail in the field.

Here’s a structured approach used on qualification benches.

- Reverse-injection test.

Feed −V in through a current-limited supply. Confirm that current stays below leakage spec — typically microamps for a PFET and a few hundred for a Schottky.

- Thermal mapping.

Run the circuit at nominal load for ten minutes, measure junction area with a small thermocouple or thermal camera. A healthy design keeps temperature rise under 40 °C above ambient.

- Step-load and plug-pull.

Sudden connection or disconnection causes short surges on long cables. Monitor with a 100 MHz oscilloscope: if voltage dips more than 200 mV or spikes above 1 V on a 5 V rail, add snubbers or gate resistors.

- Brown-out observation.

Drop supply voltage slowly while logging output. The protected node should follow input minus drop smoothly until the regulator falls out of regulation. Any oscillation signals too much trace inductance or poor ground return.

- Transient record.

For automotive-like environments, inject a 24 V / 100 ms surge while protection is active. A correct layout limits overshoot and recovers without latch-up.

Designers who already work on high-side converter tuning — as covered in TEJTE’s 5 V→12 V Boost Converter Design in Practice — will recognize the same principle: test the dynamic, not just the static.

During production validation, we also simulate “accidental plug reversal” using a custom harness with polarity-flipping switches. It catches assembly errors long before boards reach customers.

Finally, keep the test record as part of the device file; certification reviewers increasingly ask for it under safety standards like UL 62368.

8 What Assembly Checks and BOM Alternates Should I Plan

Even a flawless schematic fails if the part is placed backward or substituted without review.

Production experience suggests three layers of defense.

8.1 Assembly and Process Controls

- Polarity verification. AOI cameras must recognize the diode’s cathode stripe; teach the pattern explicitly for each package size.

- Reflow window. Follow the manufacturer’s recommended curve; an overheated tiny diode can leak before the board ever powers up.

- Visual inspection. On SOD-323F footprints, mis-alignment as small as 0.2 mm can cause open joints after thermal cycling.

Adding a simple electrical test — applying 1 V through a current-limited source — after reflow immediately flags reversed parts. This 3-second check has prevented entire reel scrap on multiple builds.

8.2 Second-Source and Field Replacement

| Parameter | Typical Value | Engineering Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse voltage rating | ≥ 20 V | Leave 2× margin over nominal input |

| Forward current | ≥ 1.5× operating current | Prevent overstress under surge |

| Forward drop | ≤ 0.5 V (1 A) | Directly affects brown-out margin |

| Leakage | ≤ 200 μA | Important for battery systems |

| Package footprint | SOD-323F / SMA | Match pad and thermal path |

For PFET stages, keep RDS(on) under 60 mΩ and gate threshold between −1 V and −3 V to ensure full conduction at logic levels.

Documenting these numbers lets purchasing substitute parts without engineer intervention — an overlooked advantage during component shortages.

8.3 Preventive Design for Field Repair

In field service, technicians replace boards faster than components. Still, adding simple cues helps:

- Silk arrows marking current flow on the PCB save confusion.

- Test pads on source and drain nodes let you verify orientation without desoldering.

- Accessible fuse placement ensures that, if reverse polarity still occurs, the repair involves a fuse not a board swap.

8.4 Insurance Through Testing and Documentation

FAQ — Practical Questions from Engineers

Q1 Does a Schottky reverse polarity diode cause brown-out at cold start?

Yes, particularly on 5 V rails where a 0.5 V drop equals 10 %. In our tests, systems that failed startup under −10 °C ambient recovered immediately after switching to PFET protection.

Q2 How do I estimate heat rise on a SOD-323F diode at 12 V / 0.25 A?

Multiply drop (≈ 0.45 V) by current to get 0.11 W, then multiply by 250 °C/W for roughly 28 °C rise — acceptable only if ambient stays below 50 °C.

Q3 When should I replace the diode with a PFET?

When loss exceeds 5 % of load power or output falls below regulator margin. It often happens near the 0.5 A level on 5 V designs.

Q4 Can I combine reverse polarity protection with a TVS clamp?

Yes, but sequence matters: current should hit the polarity block first, then the TVS handles surge energy. Reversing them leads to false conduction during transient tests.

Q5 What layout errors cause SOD-323F parts to fail reflow inspection?

Unequal copper under pads causes tombstoning; always keep symmetrical pour and avoid single-pad thermal reliefs.

Q6 How can I validate tolerance without damaging a bench supply?

Use a current-limited source and an inline ammeter; apply reverse voltage slowly up to −12 V. Leakage should stay below 1 mA.

Q7 What’s the simplest way to add dual-source power OR-ing while keeping reverse protection?

Place each PFET-based input path ahead of a controller or diode OR-ing pair. The upstream MOSFET handles polarity, the downstream network manages source selection.

Closing Remarks

Designing reverse-polarity protection may look like a formality, yet it determines long-term reliability more than any decorative EMI filter. A board that survives a user’s mistake once earns back its cost many times over.

From small Schottky diodes to PFET gates and ideal-diode controllers, every step up the ladder trades simplicity for efficiency. Knowing where your project sits on that curve is the essence of good design.

In TEJTE’s broader power-management work, including analyses like the 5 V→12 V Boost Converter Design in Practice and the MC34063 DC-DC Guide, the same theme repeats: the smallest junction often decides the largest outcome. Reverse polarity protection is simply where that lesson begins.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.