SMA Connector Panel Mounting & RP-SMA ID Guide

Dec 23,2025

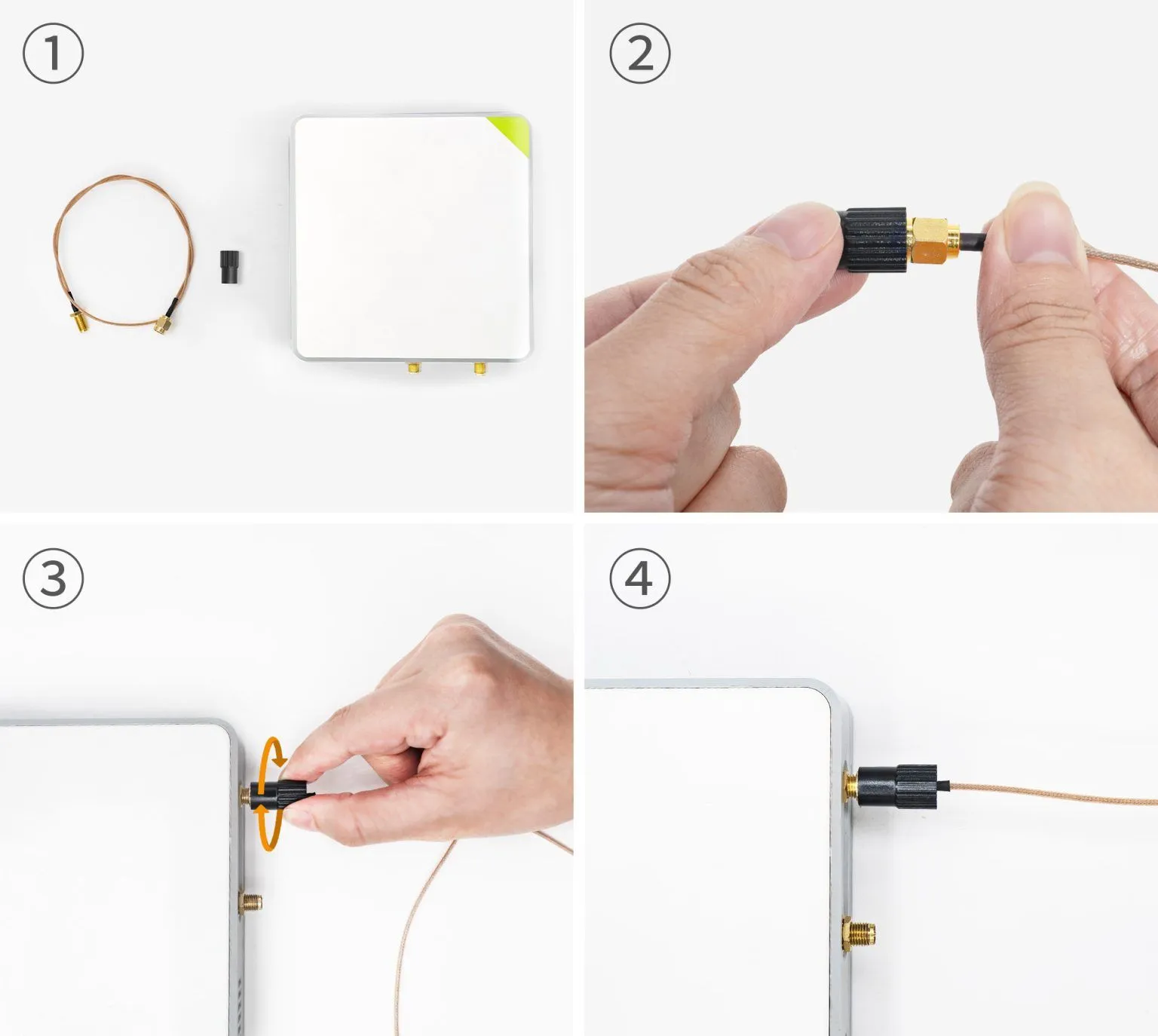

This figure is located below the title on the first page, serving as a visual introduction to the entire guide. It is likely a composite or scene image that vividly depicts typical dilemmas engineers or users might face when installing antenna cables: for example, several SMA/RP-SMA connectors that look similar but have different polarities scattered on a desk, an antenna that won't screw into a device port, or thread mismatch issues during panel mounting. Its purpose is to immediately highlight the theme, resonate with the reader about the core pain point of "minor mismatch causing major frustration," and introduce the identification, selection, and installation methods that will be systematically addressed later.

Is my port SMA or RP-SMA — how do I tell in 10 seconds?

The illustration highlights why misidentifying polarity can cause Wi-Fi/IoT connectors to fail mating.

Every technician has faced it: the connectors look identical, yet they won’t mate. That confusion almost always traces back to SMA vs RP-SMA. Both share the same 6.35 mm (¼-inch) thread diameter, but they differ in the center conductor and gender labeling.

The simplest test is what TEJTE’s engineers call the four-quadrant check. You look at two things together — the thread and the center pin — and you’ll know exactly what you’re holding.

| Thread Type | Center Feature | Connector Type | Typical Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| External thread | Pin | SMA-Male | Cable or adapter end |

| Internal thread | Hole | SMA-Female | Device chassis port |

| External thread | Hole | RP-SMA-Male | Wi-Fi antenna base |

| Internal thread | Pin | RP-SMA-Female | Router or access point port |

A quick rule of thumb: external thread with a pin equals SMA-Male; internal thread with a pin equals RP-SMA-Female. Once you remember that pairing, you can identify either type in seconds — no tools required.

For more visuals and compatibility notes, check TEJTE’s detailed reference on how to avoid RP-SMA mismatch.

Why consumer routers and APs still use RP-SMA

This figure is located in the section explaining "Why consumer routers and APs still use RP-SMA." It is an application scenario image, likely showing close-ups of three or four common consumer electronic devices, such as the antenna ports on the back of a home wireless router, the antenna base of a wireless security camera, and the connector on a mini PCIe Wi-Fi card. The figure highlights the RP-SMA female ports (typically with internal threads and a center pin) or the matching RP-SMA male antennas on these devices. This figure aims to visually illustrate the widespread presence and historical continuity of RP-SMA connectors in the consumer market through real-world examples, helping users understand that their devices likely belong to the RP-SMA system, thereby making the correct choices when selecting antennas or cables.

If you work with home routers, you’ve probably noticed that most still feature RP-SMA connectors. This isn’t an accident — it’s a habit left over from early U.S. FCC rules. In the late 1990s, Wi-Fi manufacturers adopted Reverse-Polarity SMA to discourage users from attaching unauthorized high-gain antennas. Those rules have since faded, but the supply chain inertia never did.

Today, consumer networking equipment sticks with RP-SMA by tradition, while industrial IoT gateways and cellular modems standardize on regular SMA. Knowing which family your device belongs to is the first step in avoiding a gender mismatch.

How do I match ends without a male/female mismatch?

A gender mismatch happens when both sides have either pins or holes. It’s one of the top reasons customers send back perfectly good SMA cables. The key is understanding that gender naming is mechanical, not electrical — and the labeling flips between SMA and RP-SMA families.

Always check both:

- Whether the connector has an internal or external thread.

- Whether it carries a pin or a socket.

This combination defines which side should mate with which.

When to use male-to-female vs male-to-male

This figure appears in the discussion of "How do I match ends without a male/female mismatch?" and "When to use male-to-female vs male-to-male?". It is a connection schematic that clearly shows a very common connection scenario: a female SMA or RP-SMA port (internal threads) on a device chassis (e.g., a router) is connected to a male connector on an external antenna (external threads) via a male-to-female extension cable. The figure uses arrows or lines to clearly indicate the signal flow and physical connection. This figure aims to resolve users' confusion about choosing the gender for both ends of the cable even after determining the connector polarity, ensuring the correct establishment of the signal path through a visualized standard connection method.

The most common setup uses a male-to-female SMA extension. Routers and embedded boards typically have female connectors (internal thread and center hole). External antennas, on the other hand, usually come with male connectors (external thread and center pin). The extension cable bridges the two.

A male-to-male jumper, by contrast, appears mostly in test benches or rack setups, where two bulkhead connectors need to be linked. It’s less common in deployed systems because it provides no strain relief and can increase wear on the panel threads.

If you ever wonder which side should go where, remember: female stays with the chassis, male faces the outside world.

Extension vs adapter — hidden loss and mechanical risk

This figure appears as a warning in the section "Extension vs adapter — hidden loss and mechanical risk." It is a schematic diagram, possibly showing two or three SMA adapters connected in series, forming a rigid or bent "chain." The figure uses icons or annotations to visually represent the ~0.2 dB insertion loss introduced by each adapter interface (possibly indicated by attenuation symbols or numerical labels). At the same time, the diagram uses arrows or force diagrams to demonstrate how stress, when this external assembly is squeezed, twisted, or vibrated, is transmitted directly through this rigid chain of adapters to act on the solder joints or connectors on the circuit board, causing them to loosen or break. This figure strongly recommends using a single flexible pre-assembled jumper cable instead of multiple adapters to ensure both electrical performance and mechanical reliability.

Adapters are convenient until you start stacking them. Every extra junction adds roughly 0.2 dB of insertion loss, sometimes more at 5 GHz. Two adapters and a long jumper can quietly shave a full decibel off your link margin.

But the real danger isn’t only electrical — it’s mechanical. Rigid adapter chains transfer stress straight into the PCB connector, especially when the assembly gets bumped or twisted. Once the bulkhead thread loosens, no amount of torque will fix the grounding issue.

A short flexible pigtail — such as an RG178 or RG316 cable — is far safer. It cushions the joint, reduces vibration load, and gives your layout breathing room. TEJTE’s internal testing shows these assemblies maintain impedance stability within ±0.05 Ω even after 1000 mating cycles.

For more detail on cable attenuation and structure, visit TEJTE’s comprehensive coaxial loss and cable selection guide.

For panel mounting, should I choose bulkhead or flange?

This figure appears in the introduction to panel mounting selection, under the title "For panel mounting, should I choose bulkhead or flange?". It is a product comparison chart that displays four common panel-mount SMA connectors side by side: Thru-Hole, Edge Mount, Bulkhead (with nut), and 4-hole Flange. Each connector is likely shown as a product photo or wireframe diagram with a brief text label. This figure aims to allow users to see the physical form differences between various mounting methods at a glance, laying a visual foundation for the subsequent detailed discussion on choosing between the two mainstream types, Bulkhead and Flange, helping users make a preliminary selection based on chassis structure, installation convenience, and stability requirements.

Once you bring the RF signal through a metal wall or housing, you’ll need a panel-mount SMA connector. The two dominant mechanical styles are bulkhead and flange. Both terminate the same way electrically, but their mounting methods suit different environments.

A bulkhead SMA passes through a single round hole and secures with a nut and washer. It’s ideal for quick integration or field replacement. A flange-mount SMA, available in two-hole or four-hole variants, bolts directly to the surface and stays locked under vibration.

Bulkhead versions favor simplicity; flange versions favor stability. The right choice depends on how your device lives: indoor desktop gear rarely needs flange torque, while outdoor enclosures and mobile platforms absolutely do.

2-hole and 4-hole flange vs bulkhead — stability and sealing

From a mechanical standpoint, flange connectors distribute load better. Each screw takes part of the torque, preventing the connector from spinning loose during temperature swings or vibration. That also makes flange types the preferred option for IP-rated equipment.

A bulkhead connector, by contrast, relies on a single nut. If that nut loosens even slightly, your O-ring seal weakens and water ingress becomes inevitable. Thread-locking compound helps, but in production environments, screw-mounted flanges are easier to control for consistent torque.

The trade-off is assembly speed. Bulkheads install in seconds; flanges take precision alignment. If you’re dealing with outdoor masts or vehicular units, the slower method is worth it — those threads only have to fail once to ruin a whole batch.

When a waterproof cap becomes essential

This figure is located in the section "When a waterproof cap becomes essential." It is an operational or principle diagram, likely showing an SMA bulkhead connector mounted on an outdoor equipment panel. The left side or "before" state shows the port open, exposed to icons representing raindrops, moisture, or dust. The right side or "after" state shows a rubber or metal waterproof cap correctly screwed or snapped onto the SMA port, forming a sealed barrier. The figure might use arrows or contrasting colors to highlight the effect of blocked moisture/dust. This figure aims to visually communicate a simple but often overlooked maintenance point: even when not in use, exposed SMA ports require physical protection, and a waterproof cap is an extremely low-cost and highly effective solution that significantly extends connector life and maintains signal stability.

Even an idle SMA jack can be an entry point for moisture. Water travels surprisingly well through fine metal threads. The cheapest fix is also the most effective: a waterproof cap.

Anytime an SMA port sits outdoors or near humidity, cap it. It prevents corrosion, dust buildup, and detuning from surface oxidation. TEJTE’s endurance tests show that uncapped connectors exposed to salt mist lost nearly 1 dB of return-loss margin after 48 hours, while capped units stayed stable for over 500 hours.

For field installers, it’s one of those small accessories that pays for itself — much like a properly torqued washer or a label tag that never peels off.

Transition note

Up next, we’ll tackle how to measure thread length vs panel thickness, apply correct torque, and quickly estimate signal loss vs cable length — including an on-page loss calculator that simplifies decisions before ordering.

If you often wonder how long an extension cable can be before Wi-Fi range drops, stay tuned; that section ties directly to TEJTE’s WiFi antenna cable length and loss selection insights.

How do I size the thread for my panel thickness and washers?

This figure appears in response to "How do I size the thread for my panel thickness and washers?". It is an engineering schematic focusing on a cross-sectional view of a Bulkhead SMA connector about to be or partially installed through a metal panel. The figure clearly labels several key dimensions: panel thickness, O-ring thickness, washer thickness, and the total usable thread length on the connector from the flange shoulder to the end of the threads. A dashed line or annotation might also indicate the "minimum thread length required for nut engagement." This figure aims to visualize the textual calculation formula (panel thickness + seal thickness + safety margin), helping users understand that choosing a connector with insufficient thread length will lead to insecure installation or seal failure, thereby enabling correct judgment during procurement.

Ordering a bulkhead SMA connector sounds simple—until you realize half of them don’t actually fit the hole. “Standard” and “long-thread” listings often mean different things depending on the vendor. We’ve seen panels so thick that the nut barely grabs a single thread. Others leave a loose O-ring that never seals.

When you build your own chassis, it helps to know one number: how much of that thread is usable. You measure from the shoulder (where the flange stops) to the start of the threads. Most bulkhead SMA parts give you about 6–8 mm of engagement, enough for a 1.5 mm aluminum wall plus the washer and O-ring.

If your wall is thicker, don’t force it. Either choose an extended-thread version or shift to a flange-mount design. Trying to stretch a short-thread connector is how you end up with leaks and stripped nuts.

Hole size, tolerance, and stack-up clearance

Panel holes for SMA mounts usually fall around 6.3–6.5 mm diameter. That leaves a bit of clearance, just enough to avoid scratching the plating during install. Powder-coated enclosures sometimes tighten that margin, so many technicians run a quick ream before assembly.

The total “stack height” determines how much thread is left for the nut to bite. You can think of it as a quick sum:

- Metal wall ≈ 1.5 – 2 mm

- Flat washer ≈ 0.5 mm

- O-ring ≈ 0.8 mm

Together, you’ve eaten up about 3 mm. If you only have a 5 mm threaded section, that doesn’t leave much room for error. In practice, you’ll want at least two full thread turns visible after tightening. That’s the difference between a connector that holds firm through vibration and one that spins free after a few heat cycles.

Torque, re-torque, and production consistency

Ask five technicians how tight a nut should be and you’ll get five answers. The safe window for most brass SMA bulkheads sits around 0.6 – 0.8 N·m. Too loose and the body moves; too tight and the dielectric deforms. Both conditions shift the impedance.

In our own builds, we’ve learned that hand-tightening is rarely repeatable. You might think it feels “snug,” but torque varies wildly person to person. A small preset wrench makes a world of difference. On production lines, a paint dot across the nut is a cheap insurance policy—if the mark shifts, the connector has moved.

After thermal cycling, rechecking torque once the assembly cools helps catch slow gasket relaxation. It’s the sort of dull maintenance step that saves hours of debugging later.

How long can I extend before 5 GHz range begins to drop?

Every extra meter of cable eats away at your margin. People notice it most when moving from short test leads to real enclosures: suddenly Wi-Fi range shrinks or throughput dips. The physics are simple—coax loss rises with frequency and length—but designers often underestimate how quickly it adds up.

When you’re using an SMA extension cable, think in terms of budget, not just distance. Keep total attenuation under about 3 dB and most devices stay happy. Go past 4–5 dB, and you’re throwing away half your signal power.

RG178 vs RG316: not all pigtails behave the same

The two most common short jumpers, RG178 and RG316, look similar but behave differently. RG178 is lighter and bends tighter, which helps inside compact IoT boxes, yet it loses signal faster. RG316 trades that flexibility for lower loss and better mechanical stability.

Typical attenuation (per meter):

| Cable Type | 2.4 GHz | 5 GHz | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RG178 | ~1.7 dB | ~2.8 dB | Best for <0.5 m inside devices |

| RG316 | ~1.2 dB | ~2.0 dB | Standard for external jumpers |

Every extra connector pair adds roughly 0.2 dB more. You can imagine the math: two meters of RG178 with four joints equals roughly 4 dB total—enough to see a real performance dip.

For more exhaustive data tables, TEJTE keeps full attenuation curves in its coaxial loss and cable selection guide.

Connector losses and small mechanical penalties

Even the best SMA connector isn’t perfectly transparent. Minor mismatches in plating or pin tension create reflections. A clean, tight pair adds around 0.15 dB; a worn or oxidized one, closer to 0.3 dB. Add a cheap adapter in between, and you can double it.

That’s why experienced installers minimize adapter chains. One well-fitted cable is always better than three adapters strung together. If you must use an adapter, torque it lightly and keep it aligned. Every bend or strain translates directly into return loss.

Quick Loss Estimator

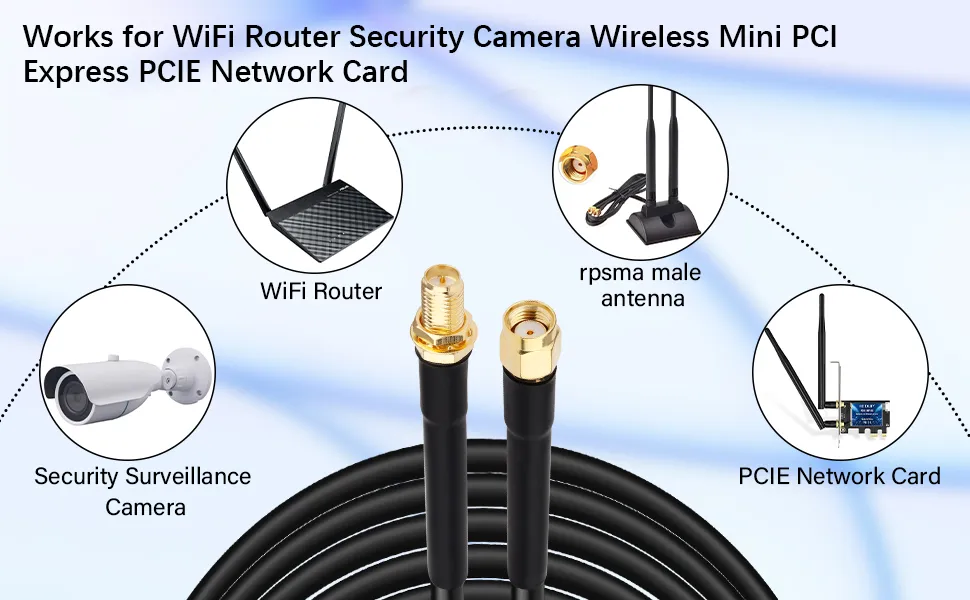

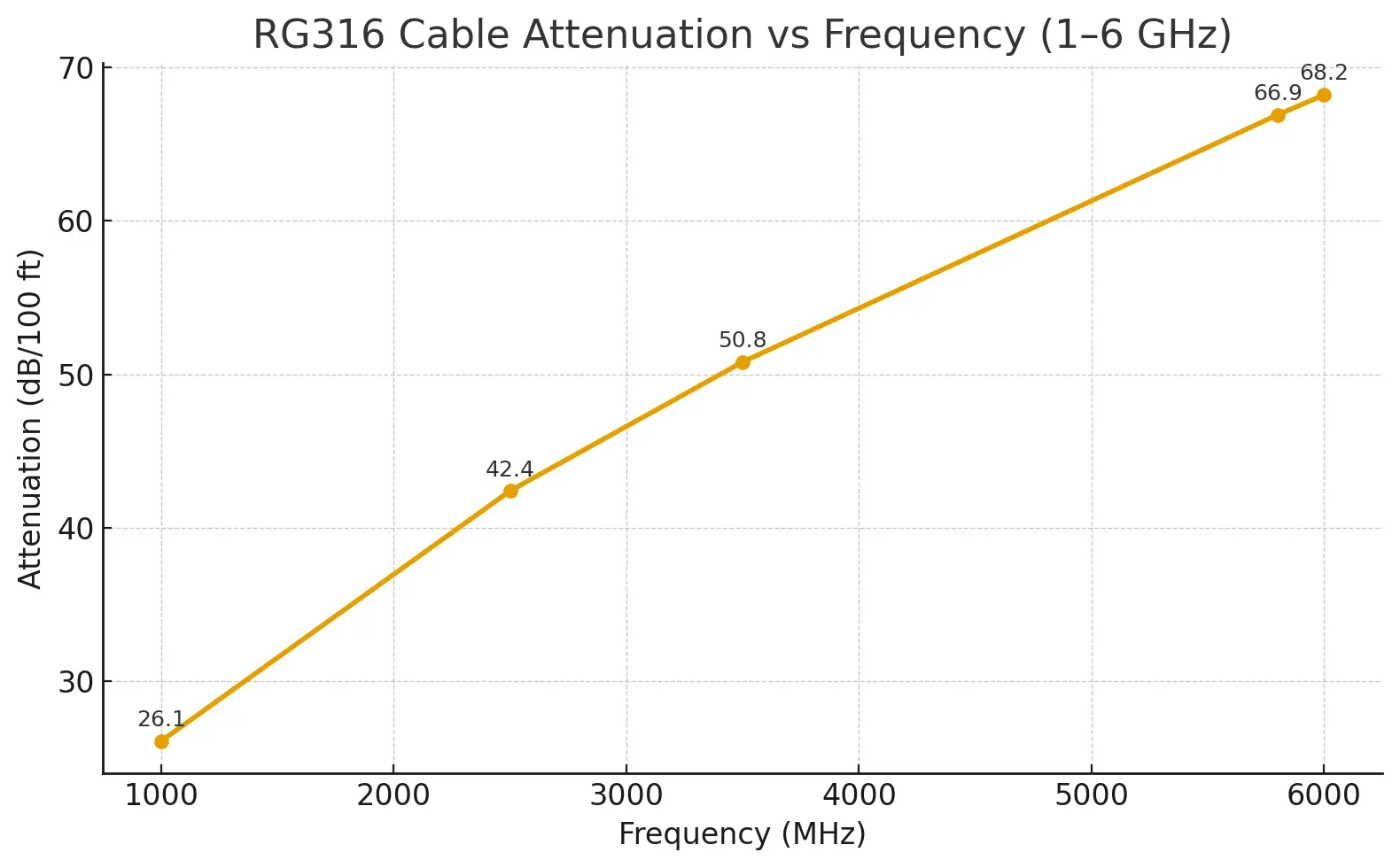

This figure is the core technical chart in the "Quick Loss Estimator" section of the document. It is a standard two-dimensional line chart where the X-axis represents Frequency, typically in MHz or GHz, ranging from 1 GHz to 6 GHz; the Y-axis represents Attenuation in dB/100 ft. The chart plots one or more attenuation curves for RG316 cable, clearly showing the trend of significantly increased signal loss with higher operating frequencies. For example, there would be a noticeable difference in attenuation values at 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz. This figure provides users with key performance data, enabling them to quantitatively evaluate the loss introduced by the cable based on the operating frequency band of their device (e.g., Wi-Fi 2.4G/5G/6G). It serves as an essential basis for link budget calculations and selecting appropriate cable lengths.

This compact model helps you guess total loss without digging through datasheets. It’s not perfect, but it’s within ±10 % of lab readings for short runs.

Formula:

Loss (dB) ≈ α(f) × L + 0.2 × n

Where:

- α(f) = attenuation coefficient (in dB/m), from your cable’s datasheet

- L = length in meters

- n = number of connector pairs

Example:

Using RG178 at 5 GHz, 1.2 m length, and two connector pairs:

Loss = 2.8 × 1.2 + 0.2 × 2 ≈ 3.76 dB

That’s roughly a 45 % power drop. For general Wi-Fi ranges, it’s acceptable. For sensitive telemetry or 5 GHz links over long distances, stay below 2 dB total.

You’ll find more context on choosing proper jumper lengths in TEJTE’s WiFi antenna cable length and loss selection.

How do I achieve IP67 sealing for outdoor or humid environments?

The correct sealing sequence

This figure is located in the section "How do I achieve IP67 sealing for outdoor or humid environments?" and is the core illustration guiding correct sealing installation. It uses a cross-sectional or exploded view to detail the complete process of achieving waterproof sealing for an SMA bulkhead connector on a panel. The figure sequentially shows each component: the connector body inserted through the panel hole, the O-ring fitted over the connector and pressed against the outside of the panel, the pressure sealing washer (possibly a star or flat washer) placed on the inside of the panel, and finally the nut tightened from the inside. Arrows and numbers clearly indicate the installation sequence. This figure emphasizes the principle that "the order matters more than most people think," ensuring the O-ring is evenly compressed between the connector flange and the panel to form an effective watertight barrier, avoiding leaks due to installation errors.

The order matters more than most people think. Start from the outside: insert the connector, seat the O-ring against the panel, add the washer, then tighten the nut from inside. Aim for even compression—enough to flatten the O-ring by about 25 – 30 % of its height.

Finish with a sealing cap if the port might sit unused. The cap isolates the thread cavity from moisture, which is the most common leak path. We’ve seen “waterproof” connectors fail simply because the installer forgot the cap.

Leak checks and gasket behavior over time

A quick soap-bubble test under 20 kPa of air pressure will show leaks long before electronics get involved. It’s simple, fast, and works anywhere. Most engineers skip it; the careful ones don’t.

Over time, gaskets relax. After the first day of temperature cycling, the torque often drops by 10 %. Re-checking torque after 24 hours prevents long-term seepage. When producing batches, use O-rings from the same hardness range; mixing durometers is a quiet way to lose sealing consistency.

Outdoor units especially benefit from silicone or fluororubber O-rings—they survive both UV and heat. For coastal or industrial zones, it’s a must.

Transition to the final section

Can I safely convert internal U.FL/IPX to an external SMA bulkhead?

This figure appears in response to "Can I safely convert internal U.FL/IPX to an external SMA bulkhead?". It is a schematic of the internal layout of a device, possibly showing an embedded Wi-Fi module (e.g., an M.2 card) mounted on a motherboard. Its U.FL micro-connector is connected via a very short (e.g., 10-15 cm) RG178 jumper cable to an SMA bulkhead connector (typically female) on the side wall of the device enclosure. The figure emphasizes protection for the U.FL connector (e.g., a label saying "~30 mating cycles"), the minimum bend radius requirement for the jumper, and the possible use of cable ties or strain relief loops to secure the jumper and prevent pulling on the fragile U.FL solder joints. This figure aims to provide a safe and reliable upgrade solution, allowing users to add a standard external antenna interface to their device while avoiding damage to the internal micro-connector.

It’s one of the most common upgrade paths for embedded Wi-Fi boards — adding an external antenna port where there wasn’t one. Internally, most modules use U.FL or IPX connectors because they’re tiny. But these micro-connectors were never designed for endless mating cycles or outdoor stress.

When converting to a panel-mounted SMA bulkhead, the key is restraint. U.FL connectors can handle roughly 30 mating cycles before contact wear causes intermittent loss. If you swap antennas frequently, move that stress to the SMA side by keeping the U.FL plugged in permanently. Use a short, flexible pigtail such as U.FL-to-SMA female bulkhead RG178 (10–15 cm).

Once installed, avoid sharp cable bends; keep a minimum bend radius of 10× the outer diameter to prevent dielectric cracking. Inside tight plastic housings, adhesive cable clips or small strain-relief loops do wonders for longevity.

Routing and EMI hygiene

In dense boards, U.FL leads often snake past power converters or high-speed data lines. Every millimeter near switching noise is an antenna waiting to happen. To minimize EMI pickup:

- Keep coax runs short and away from digital buses.

- Cross noisy traces at right angles instead of parallel.

- Ground the SMA bulkhead firmly to the chassis wall; it acts as an RF drain.

- Use the enclosure itself as a shield rather than relying on ferrite beads.

These small choices often make the difference between a design that passes FCC testing the first time and one that needs re-layout.

For step-by-step RF routing examples and loss optimization, refer back to TEJTE’s coaxial loss and cable selection guide.

What should I double-check before placing an order?

This figure is located in the section "What should I double-check before placing an order?" and is a practical tool provided by the document. It presents a clearly structured purchasing checklist table. The table columns might include "Parameter" and "Options / Description," while the rows list items that must be confirmed, such as: Connector Type (SMA/RP-SMA), Gender (Male/Female), Mounting Style (Bulkhead/2-hole flange/4-hole flange), Waterproofing (Yes/No), Cable Type (RG178/RG316/Custom), Length, Quantity, Panel Thickness/Hole Size, Use Case, etc. An example of a filled-out checklist is provided below the figure. The purpose of this checklist is to systematize the procurement process, ensuring no key details are omitted when communicating with suppliers or placing orders, thereby minimizing the risk of mismatch and returns due to unclear specifications.

Order Checklist

Below is the concise checklist you can copy straight into a purchase note.

It works for both small projects and OEM builds.

| Parameter | Options / Description |

|---|---|

| Connector Type | SMA / RP-SMA |

| Gender | Male (pin) / Female (hole) |

| Mounting Style | Bulkhead / 2-hole flange / 4-hole flange |

| Waterproofing | Yes / No (cap required?) |

| Cable Type | RG178 / RG316 / custom |

| Length | 0.05 m – 2 m |

| Quantity | (number of pieces) |

| Panel Thickness / Hole | e.g., 1.5 mm / 6.4 mm |

| Use Case | Router / AP / IoT / Industrial PC |

Output: a single-line summary ready to paste into your PO.

Example:

SMA-F bulkhead RG316 0.3 m, waterproof cap, panel 1.5 mm, for IoT gateway, qty 20.

Following this sheet eliminates over 90 % of mismatch errors and prevents the classic “pin-to-pin” return.

For cable matching and attenuation reference, cross-check with TEJTE’s WiFi antenna cable length and loss selection.

Final thoughts

This figure is located in the "Final thoughts" section of the document, aiming to reinforce the core concept of the entire guide. It is a summary infographic that likely condenses the key practices for reliably installing SMA connectors through icons, brief action points, and visual elements. Visual symbols that might be included are: a magnifying glass inspecting the connector center pin/hole, a wrench icon with a torque value, a cable forming a smooth arc indicating the minimum bend radius, a waterproof cap icon, and icons of installation steps in sequence. Together, these elements convey the message that beyond following scientific specifications like 50Ω impedance, meticulous, detailed craftsmanship and good operational habits (i.e., the "craftsman's spirit") are crucial for ensuring connectors remain reliable under long-term vibration, temperature changes, and weather exposure. This figure elevates all the technical details discussed earlier, encouraging readers to translate best practices into standard operating procedures.

Working with sma connectors is part science, part craftsmanship. On paper, it’s all about 50 Ω impedance and precise torque. In reality, it’s about thread feel, cable routing, and how much patience you have on the bench. A connector that fits perfectly today should still perform after years of vibration, heat, and weather.

The next time you assemble an antenna feedthrough or replace a pigtail, remember that small habits — checking gender, sealing properly, and respecting bend radius — make the difference between a “works fine” build and a reliable field product. TEJTE’s goal is to turn those habits into standard practice.

FAQ

1. How can I tell SMA from RP-SMA on my router without opening the case?

Look at the center pin. A router port with internal thread and a pin is RP-SMA female. If there’s a hole instead, it’s a standard SMA female. That 10-second check saves you from ordering the wrong antenna.

2. What bulkhead thread length fits a 1.5-mm aluminum panel with a gasket?

You’ll need roughly 6–8 mm of thread length. That leaves room for compression on the O-ring and washer while keeping two turns for the nut. Anything shorter may not seal correctly.

3. Will a 0.5-m SMA extension noticeably reduce 5 GHz throughput?

Typically not. With RG316 cable, expect about 1 dB loss, which is hardly visible on Wi-Fi. Range loss becomes significant only beyond one meter or when stacking adapters.

4. Can I mix an RP-SMA antenna with an SMA bulkhead using an adapter?

Electrically yes, but it adds around 0.3–0.4 dB loss and mechanical stress. For frequent connects and disconnects, use a short flexible jumper instead of a rigid adapter chain.

5. What bend radius is safe for RG178 inside a compact housing?

Stick to ≥ 10× OD (about 18 mm for RG178). Tighter curves risk cracking the dielectric, which increases return loss over time.

6. Do I need a waterproof cap for outdoor bulkhead installs?

Absolutely. Even unused ports can wick moisture through threads. A cap keeps humidity and corrosion away — a few cents that often save an entire board.

7. How many mating cycles can a U.FL connector handle before failure?

About 30 on average. After that, spring tension weakens, and signal integrity drifts. That’s why most designs treat U.FL as semi-permanent and place the SMA port outside for user access.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.