WiFi Antenna Cable Guide: SMA, RP-SMA, Bulkhead & Length Tips

Dec 22,2025

This figure is inferred to be on the first page of the document, serving as a visual index for the guide. It is likely a flowchart or schematic that outlines the core decision path for selecting a WiFi antenna cable. The figure may show the entire process starting from the internal connector (e.g., U.FL/IPX) of different devices (e.g., home routers, industrial gateways, embedded M.2 cards), through the appropriate cable and connector (e.g., SMA or RP-SMA bulkhead), and finally connecting to an external antenna. Its purpose is to provide a clear, device-type-based selection framework before users delve into the details.

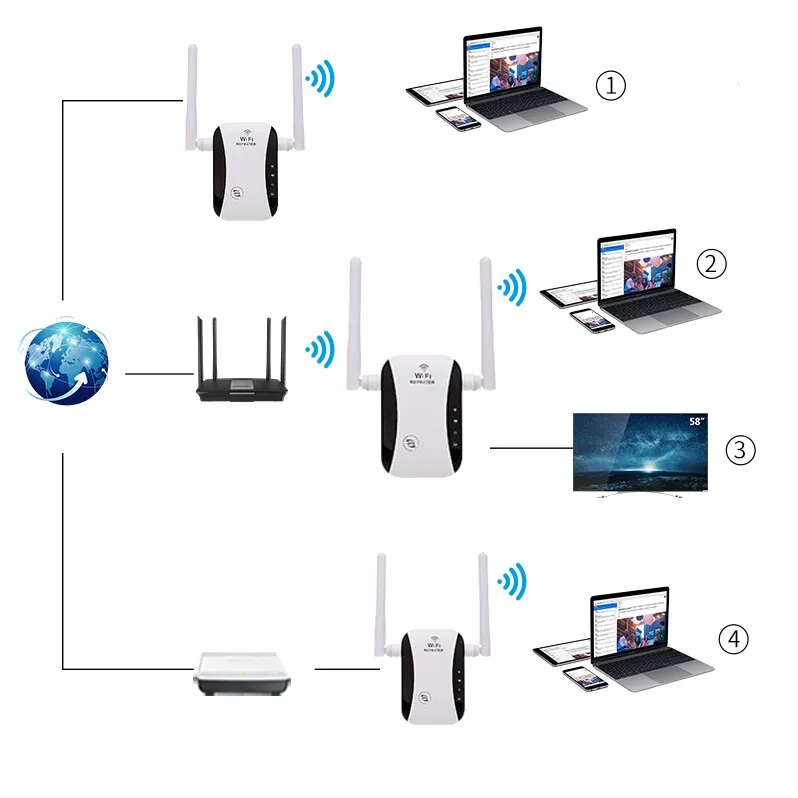

Which WiFi antenna cable do I actually need?

This figure appears in the opening section “Which WiFi antenna cable do I actually need?”. It is a scenario schematic, possibly containing multiple subfigures or annotations corresponding to devices like routers, access points (APs), IoT gateways, and mini-PCle/M.2 cards. Each subfigure would visually show the device enclosure, the micro-connector (e.g., U.FL) on the internal board, the bulkhead connector passing through the panel, and the externally connected antenna. This figure aims to help users quickly identify the “connection chain” of their own device, thereby understanding what kind of cable is needed to bridge the internal and external components.

When you start wiring a WiFi antenna cable, it’s tempting to grab anything with an SMA label. But in practice, not every cable fits — or even works. The right choice depends on what kind of device you’re dealing with and how that signal leaves your board.

Every wireless product follows its own convention. Routers and access points tend to use RP-SMA connectors, while industrial IoT gateways favor standard SMA types. Internal M.2 or mini-PCIe Wi-Fi cards use U.FL (IPX) micro connectors, which are fragile but compact. Knowing this ecosystem saves you a lot of reordering later.

Inside a router, for example, you’ll often find a short U.FL-to-RP-SMA bulkhead connector lead linking the board to the enclosure. That small pigtail defines everything — mechanical stability, return loss, and connector match. If you’re designing a product from scratch, you’ll likely build the same chain: U.FL (module) to RG178 cable to SMA bulkhead (panel) to external antenna.

For a deep dive into coax types and loss ratings, check the RG Cable Guide — it covers attenuation data you’ll need when deciding cable length.

Map device ports: SMA, RP-SMA, internal U.FL/IPX to external panel

Here’s the pattern most engineers see across devices:

- Home routers / APs: RP-SMA Female on chassis to RP-SMA Male antenna

- IoT gateways / industrial modems: SMA Female on panel to SMA Male antenna

- Embedded M.2 / mini-PCIe modules: U.FL (IPX) microjack on PCB to SMA or RP-SMA bulkhead connector

- Laptops or mini-PCs: Fixed internal antennas, not user-replaceable

Once you recognize this port family, you’ll know exactly what WiFi antenna extension cable you need. That prevents the classic “wrong gender, wrong thread” scenario that wastes days of debugging.

Common sockets: router, AP, gateway, mini-PCIe, M.2, laptop

This figure is a structured information table within the document, summarizing the antenna connection specifications for different device types. The table columns likely include “Device Type”, “Internal Connector”, “External Connector”, and “Cable Example”. It provides specific, actionable reference information, for example: Routers/APs have U.FL internally, RP-SMA-F bulkhead externally, with RG178 cable as an example; IoT gateways have U.FL internally, SMA-F bulkhead externally, with RG316 cable as an example. This table systematizes and visualizes the textual information described earlier, making it convenient for engineers and technicians to quickly consult and confirm their selection.

| Device Type | Internal Connector | External Connector | Cable Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Router / AP | U.FL | RP-SMA-F bulkhead | RP-SMA-M to RP-SMA-F RG178 cable |

| IoT Gateway | U.FL | SMA-F bulkhead | SMA-M to SMA-F RG316 cable |

| Wi-Fi Card (M.2) | U.FL | SMA-F | U.FL to SMA-F bulkhead |

| Notebook | Internal antenna | — | Non-replaceable |

SMA or RP-SMA — how do I tell and avoid mismatches?

This figure is the key visual material for solving the core question “SMA or RP–SMA?”. The figure displays close-up views of four connectors side by side, clearly labeled “SMA Male”, “SMA Female”, “RP-SMA Male”, and “RP-SMA Female”. It highlights their defining differences: standard SMA male has a center pin and outer threads, while RP-SMA male has a center hole and outer threads; standard SMA female has a center hole and inner threads, while RP-SMA female has a center pin and inner threads. This figure aims to provide an absolute reference for quick visual identification without tools, fundamentally avoiding installation failures due to connector polarity confusion.

The SMA vs RP-SMA mix-up has ruined more Wi-Fi projects than bad firmware ever did. Both look identical from the outside — same threads, same diameter — but the center pin reverses.

Here’s the simple rule:

- SMA Male to outer thread + pin

- SMA Female to inner thread + hole

- RP-SMA Male to outer thread + hole

- RP-SMA Female to inner thread + pin

That’s it. The “reverse polarity” part refers only to the center conductor.

If you compare your router and antenna together, you’ll notice that home Wi-Fi gear almost always uses RP-SMA Female ports on the chassis — that’s an inner thread with a pin in the middle. You’ll need an RP-SMA Male antenna (outer thread, hole) to mate with it.

This convention originally came from FCC rules meant to stop users from attaching high-gain antennas and exceeding EIRP limits. Even though those regulations have loosened, the hardware habit stuck.

For industrial products, though, standard SMA remains dominant. Many cellular or LoRa gateways use SMA because it aligns with test equipment and RF standards in the same 50 Ω family.

Pin-vs-hole check; compatibility matrix

| Connector | Outer Thread | Center Contact | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMA-M | Yes | Pin | Industrial antenna |

| SMA-F | No (inner) | Hole | Device panel |

| RP-SMA-M | Yes | Hole | Router cable end |

| RP-SMA-F | No (inner) | Pin | Router chassis |

Typical: home routers use RP-SMA-F (outer thread, no pin)

Look closely at any consumer router: the jack on the backplate usually has threads outside and a pin in the middle. That’s RP-SMA Female. So your antenna (or cable) must be RP-SMA Male, with a hollow center.

If you try to use a standard SMA antenna here, it’ll screw on but never make electrical contact — a common trap when mixing gear from Wi-Fi and LTE kits.

A quick trick engineers use:

“If it threads but feels dead, it’s probably RP-SMA.”

That small detail can save you from mysterious signal drops that have nothing to do with firmware or channel settings.

When should I choose a bulkhead or a flange for panel mounting?

Once you know the connector type, the next question is how it passes through your enclosure. This is where bulkhead and flange connectors come in.

A bulkhead SMA connector has a long threaded neck with a nut and washer, letting you secure it through a round hole in a metal or plastic panel. It’s quick to mount, cheap, and ideal for thin walls under 3 mm. Just slip it through, add a sealing O-ring, and tighten the nut from the inside.

A flange connector, by contrast, mounts with screws — usually two or four. It’s the go-to choice for vibration-heavy or outdoor equipment because it won’t rotate loose. You’ll find it in outdoor omni antennas and IP67 enclosures, where sealing and torque retention matter more than fast assembly.

If you’re designing an outdoor gateway, take a look at TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Guide — it shows how flange connectors pair with sealing gaskets for long-term reliability.

Thread length vs panel thickness vs gasket/cap

Here’s the rule engineers live by:

Thread length ≈ panel thickness + washer + gasket + 1 mm margin.

So, for a 1.5 mm aluminum wall with a 1 mm rubber gasket, pick a connector with at least a 3.5 mm thread. That ensures full nut engagement without bottoming out.

And if the cable is exposed to moisture, always screw a weather cap over the bulkhead when idle. It’s a cheap insurance policy that keeps your VSWR stable after a rainstorm.

2-hole/4-hole anti-loosen and sealing

When you expect vibration — think machinery, transport, or outdoor poles — the flange style wins hands down. The screws prevent spin-out and maintain gasket compression during temperature swings.

A 2-hole flange is compact and good for small IoT nodes, while 4-hole SMA flanges are standard in telecom housings rated IP65–IP67. They distribute mechanical load evenly and simplify grounding through the mounting screws.

Many TEJTE clients standardize on these 4-hole flanges across product lines because once you fix your drilling template, every assembly becomes repeatable and waterproof without extra parts.

What length is safe and how to estimate loss?

Length is the hidden enemy of every WiFi antenna extension cable.

The longer the coax, the more signal power you lose — and at 5 GHz, even half a meter can matter.

The challenge is balancing mechanical reach with RF efficiency.

For short indoor runs, RG178 cable and RG316 cable are the most common.

RG178 is thin and flexible (1.8 mm OD), making it perfect for tight enclosures.

But its attenuation climbs quickly: around 1.6 dB/m at 2.4 GHz and 2.6 dB/m at 5 GHz.

Add a couple of connectors and the loss can reach 3 dB — half your power gone.

By contrast, RG316 has slightly larger diameter (2.5 mm OD) and lower loss:

≈ 1.0 dB/m at 2.4 GHz and 1.7 dB/m at 5 GHz.

For cable runs longer than 1 m or outdoor installations, it’s often the smarter pick.

If you want more detailed attenuation comparisons across cable families,

refer to the RG Cable Guide — it lists tested loss curves, impedance data, and bend limits.

RG178 loss bands at 2.4/5 GHz; bend-radius rules

Every bend adds stress and can slightly change impedance.

Keep the bend radius at least 10 × the outer diameter.

That means for RG178, no tighter than ≈ 18 mm.

In small IoT boxes, pre-form the coax instead of sharply folding it; it reduces micro-fractures in the shield braid.

Loss example:

- 0.3 m RG178 cable @ 2.4 GHz ≈ 0.5 dB

- 0.5 m RG178 cable @ 5 GHz ≈ 1.3 dB

- 1 m RG316 cable @ 5 GHz ≈ 1.7 dB

Those numbers sound small, but every 3 dB halves the signal power.

That’s why short jumpers always outperform “any-length-fits-all” cables sold online.

Per-connector adders (~0.2 dB each)

Each additional mating pair introduces around 0.2 dB of loss.

Two connectors (both ends) = 0.4 dB, plus another 0.2–0.3 if you insert an adapter.

So, before stacking SMA-to-RP-SMA adapters, calculate if that convenience is worth the penalty.

【RG178 Quick Loss Estimator】

Fields: Frequency (2.4 / 5 GHz) | Length (m) | Connectors (n) | Adapter (Y/N)

Formula: Loss (dB) ≈ α(f) · L + 0.2 · n + (0.3 if adapter used)

| Example Case | Freq (GHz) | Length (m) | Conn. | Est. Loss (dB) | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Router pigtail | 2.4 | 0.15 | 2 | ≈ 0.5 | Negligible |

| Desktop extension | 5 | 0.5 | 2 | ≈ 1.4 | Acceptable |

| Outdoor link | 5 | 1.0 | 2 | ≈ 2.1 | Use RG316 instead |

| Lab test | 5 | 0.3 | 3 + adapter | ≈ 1.3 | Avoid extra stack |

If you stay below 1.5 dB total, you’ll rarely notice a range drop indoors.

Above 2 dB, expect shorter coverage — especially at 5 GHz, where walls eat more energy.

Male-to-female or male-to-male — how do I match the ends?

Every WiFi antenna cable has two ends that must mirror your system’s ports.

The rule is simple: the cable gender should complement the device and the antenna.

A router port marked “RP-SMA Female” means your cable end must be “RP-SMA Male.”

End-type mapping: device vs antenna

| Scenario | Device Port | Cable End A | Cable End B | Antenna Side |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Router (AP) | RP-SMA-F | RP-SMA-M | RP-SMA-F | Antenna (RP-SMA-M) |

| Industrial Gateway | SMA-F | SMA-M | SMA-F | Antenna (SMA-M) |

| Module inside case | U.FL | U.FL plug | SMA-F bulkhead | Antenna (SMA-M) |

| Lab equipment | SMA-F | SMA-M | BNC/N adapter | Test lead |

If both ends are male or both female, the line won’t physically connect.

Adapters can fix that, but each adds ≈ 0.2–0.3 dB loss — and sometimes fails IP-rating tests.

Extension vs adapter and stacked loss

An extension cable preserves gender (Male-to-Female).

An adapter changes it (Male-to-Male or Female-to-Female).

Stacking adapters is tempting during prototyping but quickly degrades the SNR.

If you need permanent flexibility, design one custom cable with the correct ends.

TEJTE’s production line often crimp-assembles SMA pigtails to ±0.5 mm tolerance — far cleaner than daisy-chained parts.

For clarity on connector family compatibility,

see the SMA vs BNC vs N-Type comparison — it explains mechanical limits and torque specs across RF standards.

Outdoor or humid installs — cap or full sealing?

When Wi-Fi gear steps outdoors, it stops being an electronics problem and becomes a weather one.

Humidity, salt, and UV destroy open SMA threads faster than any signal surge.

If you’re installing an outdoor omni antenna, add a full IP67 seal instead of just a dust cap.

That means O-ring compression, gasket spacing, and torque control.

Bulkhead + O-ring + cap stack & torque

A proper sealing sequence looks like this:

- Insert the bulkhead through the panel hole.

- Place the rubber O-ring outside the panel.

- Tighten the washer and nut from inside.

- Add a screw-on waterproof cap if the port is unused.

Torque should be firm but not excessive — around 0.6–0.8 N·m for standard SMA bulkheads.

Over-tightening compresses the O-ring too flat, reducing its long-term resilience.

More practical sealing examples appear in TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna IP67 Guide — it visualizes how the gasket, washer, and nut share pressure.

IP67 checklist

Before calling an assembly “sealed,” walk through this mini-checklist:

- Panel hole smooth, no burrs cutting O-ring.

- Washer flat against metal, no tilt.

- Gasket ≈ 25 % compressed when tightened.

- Cable strain-relieved inside enclosure.

- Cap in place if antenna absent.

That small ritual prevents moisture wicking into your RF chain.

Even a single drop of water can shift return loss by >1 dB at 5 GHz.

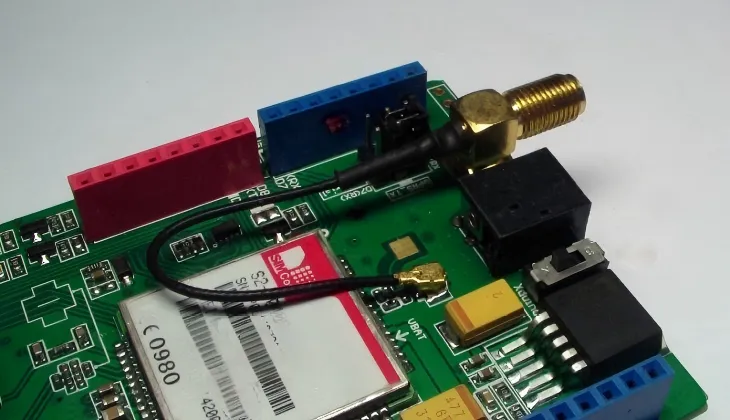

Can I safely convert an internal U.FL/IPX lead to an external SMA?

This figure is located in the section “Can I safely convert an internal U. FL/IPX lead to an external SMA?”. It is an operational schematic, possibly divided into several steps. First, it might show the fragility of the U.FL connector (limited mating cycles). Then, it focuses on demonstrating the correct procedure: using a dedicated tool (e.g., plastic spudger) to detach the U.FL plug, connecting the U.FL to a conversion cable, performing strain relief inside the enclosure (e.g., making a loop or using a clip), and finally installing the SMA connector at the other end of the cable to the bulkhead connector on the device panel. The figure emphasizes routing precautions, such as staying away from power lines and crossing at 90 degrees. This figure aims to guide users in safely and reliably completing the conversion from an internal micro-connector to an external standard interface, avoiding damage to the connector or degradation of signal integrity due to improper operation.

Yes — but do it gently.

U.FL connectors are tiny and rated for only ≈ 30 re-mates.

Beyond that, the snap ring loosens, and impedance spikes.

So if you’re routing a Wi-Fi card’s U.FL lead to an external panel, treat it as semi-permanent.

Re-mate limits and strain relief

Always use a dedicated U.FL tool or plastic spudger to detach the plug — never pull by the coax.

After connecting, loop the cable once for strain relief and fix it with Kapton tape or a nylon clip.

That way, vibration doesn’t tug directly on the pad.

Cable routing & fixation

Inside the enclosure, keep the coax away from switch-mode power lines.

DC wires can inject noise into the RF path through coupling.

Route the cable along the chassis edge and cross power traces at 90 °.

For longer extensions, secure the bulkhead with a washer on each side to distribute force.

This small mechanical detail can prevent pad lift or connector peel-off during shipment.

When done right, a U.FL-to-SMA conversion is perfectly safe — and it gives you the freedom to mount a standard external antenna without modifying your PCB.

Router/M.2 short leads — what’s the safe extension plan?

Short leads inside routers or M.2 Wi-Fi modules can be frustratingly tight.

If the internal U.FL-to-SMA pigtail is too short to reach the outer panel, extending it seems like the easy fix — but it’s not as simple as adding another cable.

A WiFi antenna extension cable adds not just length but insertion loss, and if you chain multiple pigtails, return loss can spike.

A good rule of thumb is: one jump is fine, two is risky.

Always use a single, continuous assembly that runs from the module’s U.FL to the outer SMA bulkhead.

Male-to-female extensions; recommended short lengths

For routers and gateways, choose Male-to-Female SMA extensions no longer than 0.3–0.5 m unless absolutely required.

For 2.4 GHz applications, a 0.5 m line usually costs around 1.2 dB; at 5 GHz, closer to 2 dB.

If you need more reach, consider thicker RG316 or even RG174 instead of stacking adapters.

| Use Case | Cable Type | Length (m) | Expected Loss (5 GHz) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoT module short run | RG178 cable | 0.1 – 0.3 | ≈ 0.6 dB | Ideal for small boxes |

| Router rear panel | RG316 cable | 0.3 – 0.5 | ≈ 1.5 dB | Acceptable loss |

| Outdoor AP enclosure | RG316 cable | 1.0 | ≈ 2.0 dB | Use stronger sealing |

| Test adapter | RG174 cable | 0.5 | ≈ 1.3 dB | Only for temporary setups |

2.4 GHz vs 5 GHz coverage expectations

Adding a short extension cable may slightly affect your Wi-Fi range — especially at 5 GHz, where signal wavelength is short and losses accumulate faster.

At 2.4 GHz, a 1–2 dB loss might go unnoticed indoors.

But at 5 GHz, the same drop can reduce your coverage radius by 10–15 %.

If you’re running Wi-Fi 7 or 6E hardware, note that the 6 GHz band behaves even more like 5 GHz — so keep every decibel you can.

A short, clean cable always outperforms a long, flexible one.

How do I place an error-proof order?

Even seasoned engineers occasionally order the wrong antenna cable.

Threads match, but gender doesn’t.

Connector type fits, but panel thickness exceeds the bulkhead.

To avoid all that, use a checklist before you click “Buy.”

| Field | Example | Notes / Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Connector Family | SMA / RP-SMA | Match your device: routers = RP-SMA, industrial = SMA |

| Gender (Pin/Hole) | Male (pin) / Female (hole) | Visually confirm center contact |

| Mounting Style | Bulkhead / 2-hole / 4-hole flange | Match panel thickness & torque spec |

| Waterproof Option | Yes / No | Add O-ring + cap for outdoor |

| Cable Type | RG178 / RG316 | Choose for length & flexibility |

| Length | 0.1-2 m | Keep under 0.5 m for low loss |

| Quantity | — | Verify batch needs (pairs / singles) |

| Panel Thickness | e.g., 1.5 mm | Impacts bulkhead thread choice |

| Application | Router / AP / IoT / PC | Clarify for supplier |

| Remarks | "RP-SMA M-F RG316 0.3 m IP67 bulkhead for router" | Copy into order note |

This small table may seem trivial, but it saves time and shipping costs.

Once you’ve filled it out, your vendor will have zero ambiguity.

Many TEJTE customers now embed this checklist directly into their purchase forms for WiFi antenna cable orders.

What do Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz policy changes mean for cable choices?

The RF world doesn’t stand still.

As Wi-Fi 7 spreads and 6 GHz channels open up worldwide, the expectations for antenna cables are shifting too.

Higher frequencies amplify every tiny loss and mismatch.

What felt “good enough” at 2.4 GHz may fail certification in a 6 GHz test.

Standard-power 6 GHz with AFC pilots (Cisco × Federated Wireless)

In 2025, Cisco and Federated Wireless validated Automated Frequency Coordination (AFC) for 6 GHz standard-power Wi-Fi.

That move opened the door to outdoor enterprise APs using higher EIRP limits, provided they coordinate channels dynamically.

For installers, that means better coverage — but also a need for low-loss SMA cabling that can maintain EIRP consistency.

Flimsy or overly long coax lines could push a device outside its certified margin.

(Source: Cisco & Federated Wireless joint field verification, 2025)

FCC expanded 6 GHz VLP across the entire band (effective 2025)

According to the Federal Register, the FCC has extended Very-Low-Power (VLP) operation to the entire 6 GHz range.

This gives portable Wi-Fi 7 devices more flexibility — AR headsets, laptops, and industrial handhelds can now use 6 GHz with tighter power limits.

Because transmit power is low, every dB of cable loss matters even more.

Using a properly rated RP-SMA extension cable or high-quality RG316 line becomes not just a technical preference but a compliance safeguard.

Enterprise WLAN growth and external antenna management

Market analysts at Dell’Oro Group project double-digit enterprise WLAN growth driven by Wi-Fi 7.

With more APs shipping each quarter, external antennas and cable assemblies are under new scrutiny.

Many integrators are standardizing on IP67-sealed SMA flanges to maintain performance over multi-year outdoor deployments.

If you manage enterprise installs, make a point of logging your cable type, connector family, and loss estimate during system design.

It helps you prove compliance later when regulators or clients ask for link-budget verification.

For deeper design reference, the Outdoor Omni Antenna Guide and RG Cable Guide both show how environmental and RF parameters intersect in real deployments.

Looking for Pre-tested RF Cables?

TEJTE provides precision-assembled SMA and RP-SMA WiFi antenna cables with verified insertion loss and IP67 options for both indoor and outdoor setups.

Explore our RF Cable Series or contact the TEJTE engineering team for OEM customization.

Final Word

The humble WiFi antenna cable connects more than just a signal — it ties your board, case, and antenna into one ecosystem.

Pick the right connector family, match the genders, keep the run short, and seal it well.

Each small detail builds reliability over years of operation.

Engineers often joke that antennas fail quietly, but cables fail expensively.

That’s usually true.

By taking time to calculate loss, plan bulkhead dimensions, and follow the checklist above, you’ll avoid those hidden headaches — and your RF design will perform exactly as the datasheet promised.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.