Rubber Duck Antenna: Indoor Coverage & SMA Matching in Practice

Dec 21,2025

This figure appears at the beginning of the document as an introductory visual for the entire guide. It is likely an infographic or schematic that summarizes the multiple key practical aspects to consider when selecting a rubber duck antenna, including mechanical form, electrical performance (gain), interface matching (SMA), system loss (feedline), physical placement, and final procurement validation, aiming to provide a global perspective for the detailed sections that follow.

Choosing the right rubber duck antenna can be deceptively tricky. What seems like a simple stubby rod often determines whether your Wi-Fi or IoT device keeps a stable link or drops out when you move five feet away. This guide walks through the real-world selection logic that engineers at TEJTE use daily — from form and gain to SMA matching, feeder loss, placement, and order validation.

If you’re still comparing omni models, you can also check TEJTE’s Omnidirectional Wi-Fi Antenna Selection & Coverage Guide for a broader view of outdoor and mesh setups.

Which rubber duck antenna form and gain fit your device?

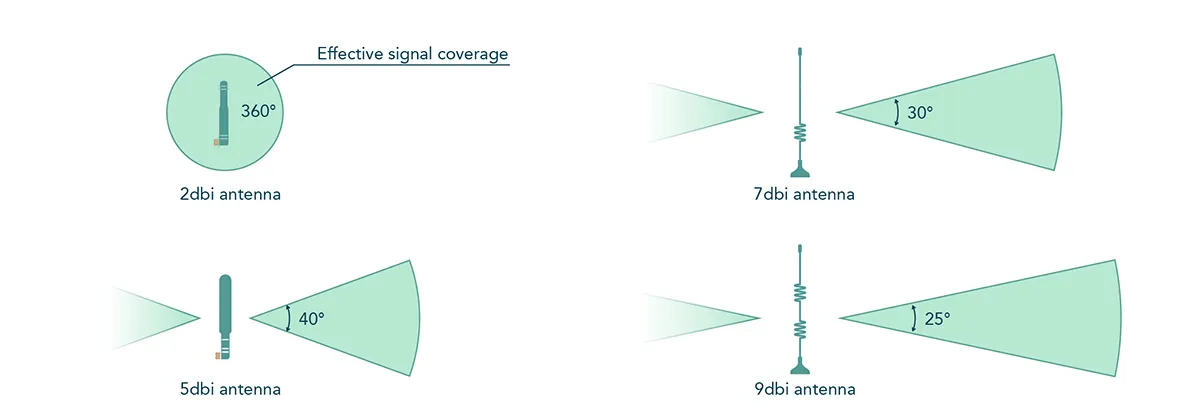

This figure immediately follows the question “Which rubber duck antenna form and gain fit your device?” It visually compares the radiation patterns of antennas at different gain values. The figure likely uses sectors, cones, or circles of varying sizes or shapes to represent the wide but short coverage “dome” of low-gain antennas (e.g., 2-3 dBi) and the narrow but long horizontal “beam” of high-gain antennas (e.g., 5-9 dBi), helping readers understand the impact of gain selection on actual coverage shape and distance.

Every engineer has a story about a so-called universal rubber duck antenna that somehow underperforms once installed. The truth? No “one-size-fits-all” exists. Your enclosure, cable routing, and even the nearby battery can shift the game.

A rubber duck antenna — that flexible omnidirectional rod seen on routers and IoT gateways — provides convenience and mechanical resilience. Yet the real secret is how well its gain and form factor align with your environment.

If your product operates in a dense, reflective space like a warehouse or retail floor, 2–3 dBi versions are usually the sweet spot. Their wider radiation lobes tolerate multipath reflections and give balanced coverage.

Need reach down a long corridor or aisle? Go for 5–6 dBi. These stretch the signal horizontally but trim elevation coverage. You’ll gain distance on the same floor while possibly losing strength above and below.

| Gain Range (dBi) | Typical Use Case | Effective Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| 2-3 dBi | Compact enclosures, IoT gateways | Broad dome, short reach |

| 5-6 dBi | Corridors, mesh APs | Narrower beam, longer horizontal coverage |

| ≥ 8 dBi | Specialized / semi-directional | Flattened beam, fragile near metal |

Choose straight vs right-angle (I/L type) and bendable shafts for clearance

Mechanical clearance matters as much as RF performance. Straight “I-type” antennas suit upward-facing SMA connectors on open boards. Right-angle (L-type) models fit better for side-mounted jacks or rack equipment.

Bendable shafts help adjust radiation away from nearby metal. In TEJTE’s lab trials, bending outward by 20° recovered 2–3 dB RSSI compared to a rigid stick pressed against a chassis wall.

Tip: Keep at least 20 mm clearance from large ground planes or screws. Even small overlaps can shift resonance by 50–80 MHz.

If you’re designing the board layout itself, the 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi Antenna Selection & Ordering Guide provides more insight into placement and tuning rules.

How do you confirm SMA vs RP-SMA in 5 seconds and avoid mis-orders?

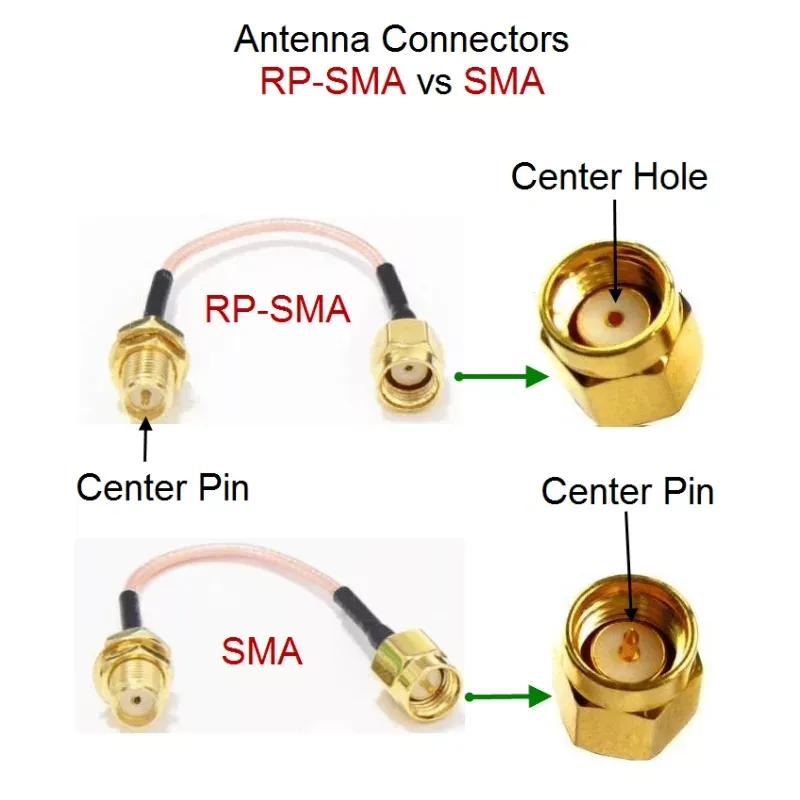

This figure is the core illustration in the section “How do you confirm SMA vs RP–SMA in 5 seconds and avoid mis-orders?”. Through a cross-sectional or close-up view, it clearly shows the physical characteristics of four key connectors: standard SMA male (with center pin), standard SMA female (with center hole), RP-SMA male (without center pin, has a hole), and RP-SMA female (with center pin). This figure serves as a direct reference for quick visual identification, aiming to solve the common problem of connector confusion in engineering.

Pin/hole quick ID, gender pitfalls, bulkhead feedthrough basics

- SMA Male: Has a center pin and outer threads.

- SMA Female: Has a center receptacle (hole) and inner threads.

- RP-SMA Male: Has no pin, outer threads (reversed polarity).

- RP-SMA Female: Has a center pin but inner threads.

To remember fast: Pin = Male for standard SMA; Pin = Female for RP-SMA.

Bulkhead versions may flip relative to cable assemblies, so confirm both ends before ordering. Many TEJTE clients now attach labeled photos per SKU — preventing SMA to RP confusion during bulk builds.

Labeling and color codes for lab spares and field swaps

In field kits, color-coding saves chaos. For instance:

- Black boots to SMA

- Gray to RP-SMA

- Blue to reverse-gender sample

Add a small heat-shrink label like “2 dBi SMA-M” or “6 dBi RP-SMA-F”. QR stickers linking to TEJTE datasheets make replacements fool-proof.

Most engineers maintain 20–30 antennas in bins; clear labeling avoids deploying the wrong type during maintenance.

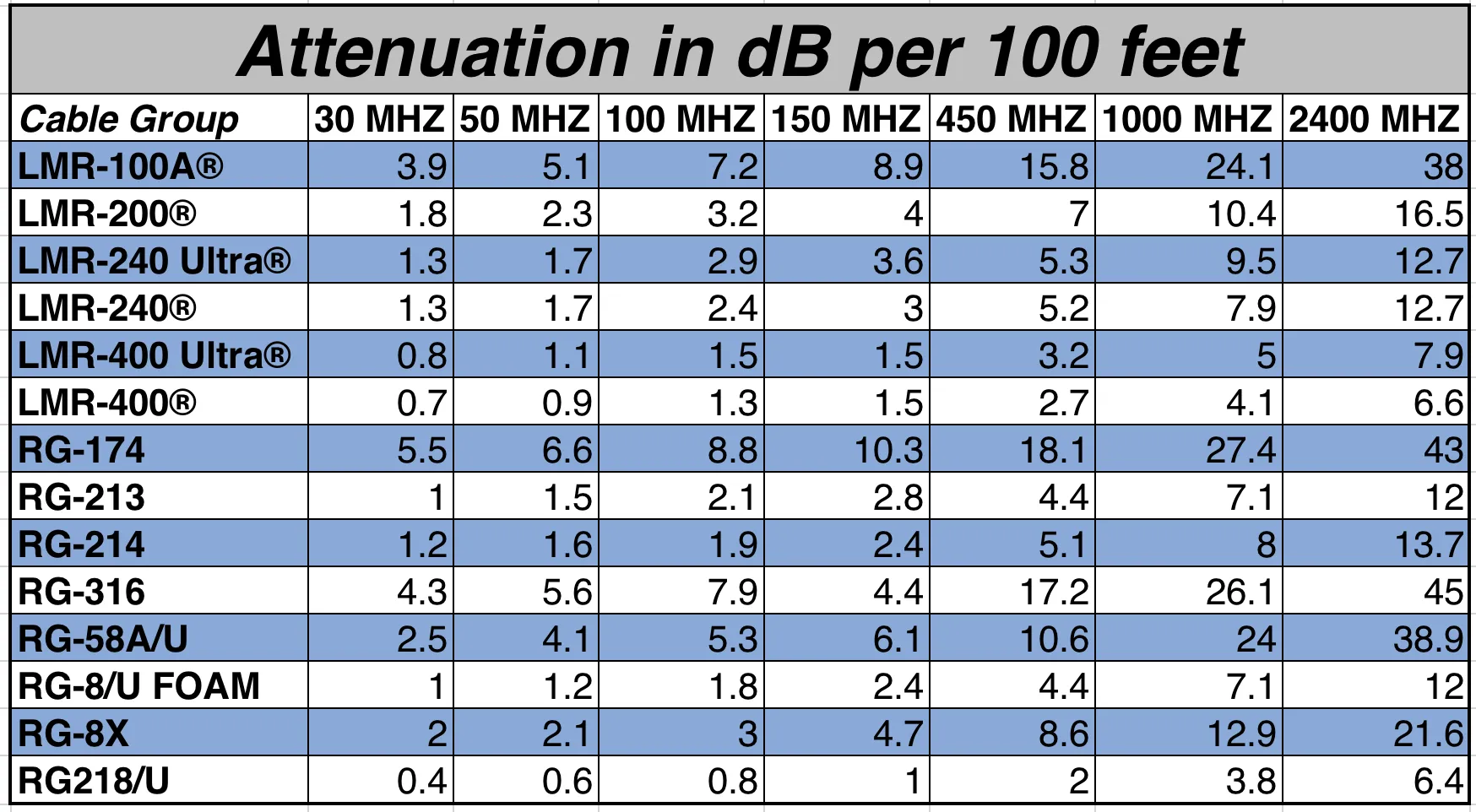

Will your feeder type and length quietly erase 2.4 GHz gains?

Cable type, loss, and realistic trade-offs

| Cable Type | OD (mm) | Loss @ 2.4 GHz (dB/m) | Flexibility | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.81 mm micro-coax | 0.81 | ≈ 0.80 | Very high | Internal PCB to SMA pigtails |

| 1.13 mm micro-coax | 1.13 | ≈ 0.60 | High | Compact IoT modules |

| LMR-240 | 6.1 | ≈ 0.26 | Medium | Router extensions < 3 m |

| LMR-400 | 10.3 | ≈ 0.14 | Low | Outdoor or lab jumpers |

This figure is located in the section discussing feeder type and loss. It is a comprehensive data table with frequency (e.g., 30 MHz, 2.4 GHz) as column headers and cable models (e.g., LMR-400, RG-58) as row headers. The table cells contain specific attenuation values. This figure provides engineers with key performance reference data when selecting feeder cables, visually showing the loss differences among various cables at different frequencies, especially for key bands like 2.4 GHz, aiding in link budget calculations.

Count connector pairs and evaluate VSWR near plastics and brackets

Each connector introduces small mismatch loss (~0.15 dB per pair). Cheap plating or loose torque can worsen reflection.

Plastic housings or brackets close to the antenna detune impedance too. In TEJTE tests, adding a thin decorative shell raised VSWR from 1.3 to 1.7, cutting usable gain by 1 dB.

Before freezing your BOM, measure S11 with a VNA. One clean dip at 2.4 GHz = good; multiple dips = coupling or poor feed design.

Where should you place a rubber duck to avoid metal detuning and shadowing?

This figure appears at the beginning of the chapter “Where should you place a rubber duck to avoid metal detuning and shadowing?”. It is likely a schematic diagram showing a rubber duck antenna model placed too close to a block representing a metal object (e.g., battery, chassis wall). The figure may use distorted wave lines or altered radiation lobes to visually represent the “detuning” phenomenon caused by electromagnetic coupling, where the antenna’s resonant frequency and impedance matching shift, leading to a drop in signal strength (RSSI).

Even the best rubber duck antenna can’t escape physics. When installed too close to metal, it changes its shape electrically — a phenomenon called detuning. The result? Your return loss curve shifts, the matching disappears, and RSSI drops like a stone.

Metal surfaces, batteries, and shield cans all act as parasitic reflectors. At 2.4 GHz, even a small ground plate can absorb or reflect energy within 10–20 mm of the antenna base. That’s why placement deserves the same attention as connector choice.

Ground-clear rules around batteries, shields, and rails

Engineers at TEJTE often follow a simple spacing checklist:

- ≥ 15 mm from battery packs or large aluminum frames.

- ≥ 20 mm from shield cans or copper planes.

- ≥ 10 mm from rails or screws running parallel to the antenna axis.

If you can’t meet those distances, try bending the antenna slightly outward. In field setups, even a 15-degree tilt often brings back 1–2 dB of signal strength.

Another overlooked issue is enclosure plastic. Thick ABS walls with metallic paint can shift resonance by 50 MHz. Always measure one assembled unit before production. A simple network analyzer sweep saves weeks of customer complaints.

If your design integrates multiple antennas, see TEJTE’s Wi-Fi Antenna Guide: 433 MHz, 4G, 5G, GSM & SMA Types to check coexistence and clearance rules between close-coupled radiators.

Coexistence spacing with other antennas (CCI / ACI / MIMO symmetry)

This figure is located in the “Coexistence spacing with other antennas” section. It likely shows a simplified top or side view of a device enclosure with two or more rubber duck antennas installed. The figure would use arrows, dimension lines, or annotations (e.g., “≥ 30 mm”, “≥ 0.25λ”) to clearly indicate the recommended minimum distance between antenna centers. This figure aims to provide intuitive layout guidance, helping engineers avoid mutual interference (CCI/ACI) problems caused by antennas being too close during the design phase.

When multiple radios share one enclosure — Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, cellular, LoRa — spacing is key. At 2.4 GHz, you’ll want at least 0.25 λ (~30 mm) between antenna centers to minimize co-channel interference (CCI).

For MIMO systems, symmetric positioning improves phase correlation and throughput. TEJTE typically keeps each antenna at ≥ 40 mm separation when using two rubber ducks on a dual-band AP.

Do you really need an outdoor omni instead of a rubber duck in semi-outdoor areas?

IP / UV limits, weatherproof boots, and quick drip-loop routing

This figure appears when discussing the limitations of using rubber duck antennas in semi-outdoor areas. It is an operational schematic showing how an antenna feeder cable exits from the device (or antenna base), first goes down to form a “U” shaped arc (the drip loop), and then goes up or horizontally. The figure highlights this lowest point and may show the use of heat-shrink tubing, self-amalgamating tape, or rubber boots for sealing at the connector interface. This figure visually conveys the key installation technique to prevent rainwater from flowing along the cable into the device.

Most rubber ducks are rated around IP30–IP40 — basically dust-resistant, not waterproof. Prolonged UV exposure hardens the plastic, causing cracks in less than a year.

When partial exposure is unavoidable, use rubber sealing boots, heat-shrink sleeves, or self-amalgamating tape at the base joint.

Route the cable downward with a drip loop, preventing water from entering the SMA bulkhead. It’s a simple yet often-ignored step that extends lifespan dramatically.

In humid climates, condensation is worse than rain. If you notice unstable RSSI during dawn hours, moisture inside the antenna sleeve is likely the cause. Once wet, it never performs the same. Replace immediately.

When directional or mast-mount beats a rubber duck despite convenience

If your device must serve open courtyards or warehouse loading bays, switch to a proper outdoor omni antenna or even a mast-mount antenna. They come with UV-rated fiberglass bodies and IP67 sealing.

A quick rule from TEJTE’s field projects:

- For semi-outdoor corridors, rubber duck = temporary OK.

- For roof eaves or poles, use Mast Mount Antenna Installation & IP Sealing Field Guide as your blueprint.

Those designs withstand wind and rain while keeping VSWR stable below 1.5:1 across bands. Rubber ducks simply can’t match that endurance.

Can you validate coverage fast before freezing the BOM?

RSSI / throughput snapshots, elevation-null checks, quick heatmaps

Walk tests are still gold. Place your device at the intended installation height and measure RSSI at several points. Use free software like Wi-Fi Analyzer or inSSIDer.

Plot throughput (Mbps) or latency per distance. In open rooms, a well-matched 3 dBi antenna should maintain > –65 dBm at 10 m.

If you observe dips above and below the device plane, you’ve hit the elevation null typical of 5 – 6 dBi models. Slight tilting or relocation fixes it.

Quick heatmaps created from smartphone apps or lightweight scanners show shadow zones immediately. Many TEJTE customers now log before / after RSSI maps as part of acceptance testing.

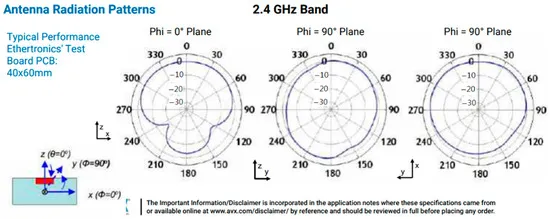

Cable-first fault isolation: cable to connector to antenna swap

This figure is located in the “validate coverage fast” section, before discussing fault isolation. It is a professional RF test result graph presented in polar coordinates. The figure contains two subplots corresponding to the radiation patterns in the horizontal plane (Phi=0°) and vertical plane (Phi=90°). Concentric circles represent gain levels (e.g., 0dBi, -10dBi, -20dBi), and curves radiating from the center show signal strength variation with azimuth or elevation angle. This figure is used to illustrate the actual radiation characteristics of a rubber duck antenna, likely from a manufacturer’s test report, serving as objective evidence for evaluating antenna performance.

If signal fluctuates, isolate one piece at a time:

- Replace cable only to re-measure.

- Swap connectors to re-measure.

- Finally, change antenna.

In over half of reported “antenna failures,” the culprit was actually a micro-coax break or oxidized SMA threads. Regular torque checks (0.6 – 0.8 Nm for SMA) prevent that.

2.4 GHz Rubber-Duck Link-Budget Mini-Calculator

This figure is a core illustration directly related to product performance, appearing before the “validate coverage fast” and fault isolation steps. It is not a generic schematic, but a measured result chart from a specific test environment (noted as based on an Ethertronics 40x60mm test board). The core part of the figure is the polar radiation pattern, showing the gain variation with angle in the horizontal plane (Phi = 0°) and vertical plane (Phi = 90°) respectively. Concentric circles represent gain levels (e.g., 0, -10, -20 dB), and the pattern shape visually reflects the coverage characteristics of this antenna model in actual operation. The figure or its caption typically also includes key performance claims or typical specification parameters for this antenna product, such as frequency band, gain range, VSWR, etc. The purpose of this figure is to provide engineers and purchasers with objective performance data of this specific product under standard test conditions, used to assess whether it meets the coverage requirements of the design. It serves as direct evidence for product selection and specification verification.

| Parameter | Symbol / Formula | Typical Value / Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmit Power | tx_power_dBm | 15 – 20 dBm | Output of Wi-Fi or IoT module |

| Antenna Gain | antenna_gain_dBi | 2 / 3 / 5 / 6 dBi | Based on rubber-duck type |

| Feeder Type | feeder_type | 0.81 / 1.13 / LMR-240 / LMR-400 | Cable selection |

| Feeder Length | feeder_length_m | 0.1 – 3 m | Total jumper length |

| Connector Pairs | connector_pairs | 1 – 2 | SMA joins per path |

| Feeder Loss | feeder_loss = loss_per_m × length + 0.15 × pairs | — | Total cable attenuation |

| EIRP | EIRP = tx_power_dBm - feeder_loss + antenna_gain_dBi | — | Effective radiated power |

| Path Loss | path_loss_dB | Calculated / measured | FSPL or real measurement |

| Receiver Sensitivity | rx_sensitivity_dBm | -90 ~ -70 dBm | Device threshold |

| Link Margin | link_margin = EIRP - path_loss_dB - rx_sensitivity_dBm | — | Positive = OK, Negative = Fail |

Typical Loss @ 2.4 GHz:

0.81 ≈ 0.80 dB/m | 1.13 ≈ 0.60 dB/m | LMR-240 ≈ 0.26 dB/m | LMR-400 ≈ 0.14 dB/m | connector pair ≈ 0.15 dB

Rule of thumb:

- link_margin < 6 dB to adjust setup: shorten or upgrade cable, reduce connectors, or relocate antenna.

- link_margin > 15 dB to stable design: proceed to environmental testing.

For the underlying propagation math, reference the Free-space path loss model. TEJTE’s internal calculator tool uses the same principle for pre-deployment checks.

Should you standardize PO fields so the build is fool-proof?

Most purchasing mistakes in antenna orders aren’t caused by suppliers — they start at the purchase order (PO). Engineers assume part numbers are self-explanatory, yet small details like “RP-SMA vs SMA” or “5 dBi vs 3 dBi” create silent chaos in logistics.

When you standardize your PO template, you eliminate guesswork for everyone — the buyer, the assembler, and the supplier. TEJTE recommends locking down every parameter relevant to RF and mechanical fit before the first batch leaves the dock.

Required order fields (gain / length / connector / angle / cable / labels)

A complete antenna PO should capture:

- Gain and type: e.g., Rubber Duck Antenna 3 dBi, 2.4 GHz.

- Connector: SMA-M, RP-SMA-F, or custom bulkhead feedthrough.

- Angle / form: straight, right-angle, or bendable.

- Cable assembly (if any): type, length, connector at far end.

- Labeling / packaging: printed frequency, color-coded cap, TEJTE logo.

Compliance items also matter — RoHS / REACH status, torque hints (0.6–0.8 Nm), and packaging marks for RMA traceability. Many TEJTE clients include a small QR tag on the bag linking directly to the TEJTE Rubber Duck Antenna product category, so inspectors can verify specs instantly.

Rubber-Duck Ordering & Acceptance Checklist

Below is the checklist TEJTE’s procurement and QA teams use during RF antenna orders.

You can turn it into a digital form or shared Google Sheet for your team.

| Item | Details / Example | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Antenna gain / length | 2 dBi, 50 mm | Spec sheet or labeling |

| Connector type | SMA-M / RP-SMA-F | Visual / pin check |

| Angle type | Straight / Right-angle / Bendable | Visual |

| Cable (type / length) | 1.13 mm, 150 mm | Measured |

| Label / trace | Printed band, QR, TEJTE tag | Visual scan |

| RoHS / REACH | Yes | Cert check |

| Torque hint | 0.6-0.8 N·m | Mech spec |

| Packaging | TEJTE sealed bag | Visual |

| RMA mark | Batch number / barcode | Database |

| RSSI proof | ≥ -65 dBm @ 10 m | Test log |

| Photo record | Unit + setup photo | QA doc |

Best practice: before shipment, TEJTE QA captures a quick RSSI snapshot with a reference router. A single screenshot showing stable throughput is more convincing than a paragraph in an email.

If your project involves mixed frequencies (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz), consider cross-linking your form to the Wi-Fi Antenna Coverage & Selection Guide — it helps verify gain and connector compatibility during procurement.

Wi-Fi 7 tri-band clients and the persistence of 2.4 GHz for IoT

With Wi-Fi 7 introducing tri-band clients, many thought 2.4 GHz would fade out. Instead, it’s now reserved for IoT reach and low-power standby links.

Smart plugs, sensors, and industrial controllers still rely on it for longer range and better wall penetration. Rubber duck antennas remain ideal for such low-power nodes thanks to their compact form and forgiving impedance match.

Meanwhile, shorter LMR jumpers have replaced thin micro-coax tails in many designs. Field engineers found that the extra stiffness is a small price for stable VSWR and fewer connector failures.

More standardized elbows and adapters reducing field variance

In 2025, several OEMs (including TEJTE’s suppliers) began shipping standardized SMA elbows with consistent dielectric alignment and lower return loss.

This minor mechanical improvement has major downstream benefits: it keeps installation torque uniform and minimizes detuning.

For installers, that means fewer unpredictable results when swapping antennas between units. The same box of spares finally behaves the same in every build.

If you’re migrating older APs to Wi-Fi 6E or 7, TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Selection & Ordering Guide explains how to upgrade while keeping backward compatibility with your 2.4 GHz rubber ducks.

In short: the ecosystem matured. The once-chaotic mix of connectors and patterns has become far more predictable — a relief for every field engineer who’s ever re-crimped a cable at 2 AM.

FAQ — rubber duck antenna

How can I tell SMA from RP-SMA in under 5 seconds without tools?

Does moving from 3 dBi to 6 dBi improve corridor coverage or create elevation nulls?

What’s the practical maximum length for 1.13 mm pigtails before loss cancels the gain?

How much spacing from metal edges and other antennas prevents detuning and coupling?

When should I switch from a rubber duck to an outdoor omni or a directional antenna?

Which quick tests (RSSI / throughput / mini heatmaps) prove the install is good before sign-off?

How do I prevent field confusion between SMA and RP-SMA units during maintenance?

Final Word

This application scenario diagram focuses on a common engineering decision point. It goes beyond pure technical parameters, introducing environmental durability as a key selection criterion. The diagram likely uses comparative illustrations to visually demonstrate the issue of plastic brittleness in rubber-duck antennas under continuous sun and rain, and the advantages brought by outdoor omni antennas through sealing, UV-resistant materials, and robust mounting methods. It emphasizes that in seemingly “semi-protected” environments, long-term reliability is often more important than initial cost, guiding readers to make selections from a product lifecycle perspective.

The rubber duck antenna may look modest, yet it remains one of the most dependable solutions for Wi-Fi and IoT devices. From clearance and gain choice to connector care and PO discipline, every detail shapes real-world performance.

When you treat antennas as precision components — not accessories — you’ll spend less time debugging and more time shipping stable products.

For comprehensive indoor–outdoor comparisons, visit TEJTE’s Wi-Fi Antenna Guide: Indoor & Outdoor Selection — a good next step before finalizing your design.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.