2.4 GHz Antenna Selection & Ordering Guide for Wi-Fi and IoT Devices

Dec 05,2025

Which 2.4 GHz antenna form factor fits your device?

Figure establishes the starting point of the document’s discussion—external antennas. Through a typical “plug-and-play” scenario, it shows readers the main advantages of such antennas (easy installation and testing, consistent directionality) and the drawbacks to consider (exposed, requiring waterproofing and strain relief design). This image provides a concrete visual reference for the subsequent comparison with internal antennas and in-depth discussions on topics like gain, cables, and connectors.

At 2.4 GHz, the antenna isn’t just a piece of metal—it defines how your Wi-Fi or IoT product performs in the real world. The first choice is always form factor: external or internal. That single decision impacts enclosure design, cable routing, and even certification margins.

External “rubber-duck” antennas remain the go-to for routers, CPEs, and gateways. Their plastic housings conceal tuned whips optimized for 2.4 GHz’s 12.5 cm wavelength, offering 2–6 dBi gain with a consistent omnidirectional pattern. Engineers love them because they’re plug-and-play: screw onto an SMA or RP-SMA port, point upright, and test. The downside? They’re exposed. If your product sits outdoors or in a handheld shell, you’ll need to plan for waterproof bulkheads and strain relief.

Figure represents the “flexibility” option among internal antenna solutions. It intuitively explains how the FPC antenna addresses antenna placement in compact spaces through its physical characteristics. The image emphasizes the suitability of this antenna for non-metallic enclosures, serving as an important visualized choice for designers balancing cost, space, and signal performance.

Figure showcases the most integrated solution in antenna design. It transforms the antenna from a separate “component” into part of the circuit board’s “pattern.” This image reminds engineers that choosing a PCB antenna shifts the core responsibility for RF performance from the antenna supplier to their own board-level design, requiring a deep understanding of how layout, stack-up, and the surrounding environment affect antenna performance.

Figure represents the forefront of antenna miniaturization. Ceramic antennas package the radiating element within a surface-mount package similar to passive components, drastically saving space. However, the solution represented by this image also implies its limitations—narrow bandwidth and strict adherence to layout guidelines (especially the ground clearance area). It is a specialized tool for specific high-performance, small-form-factor application scenarios.

In contrast, internal antennas—FPC, PCB, or ceramic—hide inside the case. An FPC antenna (flexible printed circuit) can stick to an inner wall with adhesive tape. It’s thin, light, and ideal for plastic enclosures. A PCB trace antenna saves cost and integrates directly onto your board but needs careful tuning to avoid detuning from ground planes or nearby metal. Ceramic chip antennas deliver small size and consistent impedance but often trade off bandwidth for footprint.

To match antenna type to your housing material:

- ABS or PC plastic: all internal options work; FPC gives the easiest layout freedom.

- Metal or partial-metal shells: use external or feedthrough-mounted antennas only; internal ones will suffer detuning or total loss.

- Hybrid enclosures (metal frame + plastic lid): mount the antenna behind the plastic section or use a short IPEX to SMA pigtail to bring the element outside.

There’s no universal “best.” Think of it as a budget–performance triangle: cost, space, and signal reach. Choose the corner your design can afford to lean toward.

How do you identify SMA vs RP-SMA and avoid ordering mistakes?

Figure is the core of the document’s “error-proofing guide.” It addresses a long-standing and costly pain point in RF connectivity. The image not only shows the difference but also teaches through clear visual labels (e.g., “RP-SMA”, “SMA”). Understanding this distinction is crucial for correctly connecting consumer Wi-Fi gear (often using RP-SMA) with standard RF test instruments (often using SMA). This figure is a must-know visual tool for engineers and procurement personnel.

Every engineer has ordered the wrong SMA connector at least once. It’s a rite of passage—and a costly one. The confusion stems from the “reversed polarity” used in consumer Wi-Fi gear, known as RP-SMA, which swaps the inner pin and socket between genders.

Here’s the five-second field test:

- SMA-male → has a center pin and outer threads.

- SMA-female → has a center hole and outer hex body.

- RP-SMA-male → looks the same outside (threads), but no pin inside.

- RP-SMA-female → has a pin, but no inner hole.

Why does this matter? Because mating an SMA-male with an RP-SMA-female won’t connect electrically; the inner contacts won’t touch. Many Wi-Fi modules and routers use RP-SMA-female jacks by default, while most RF instruments use SMA-female. Always verify what your device port provides before finalizing a purchase.

Beyond gender, check the geometry:

- Straight vs right-angle connectors depend on how your device faces the antenna.

- Bulkhead SMA/RP-SMA types are ideal for bringing RF lines through a panel or case wall.

- Bendable joints (hinged rubber-duck types) allow flexible orientation when signal alignment matters.

If you’re wiring from a compact PCB to a case wall, pair an IPEX/U.FL pigtail with an SMA bulkhead—just watch the loss budget when the cable exceeds 20 cm.

Tip: When in doubt, search “SMA vs RP-SMA quick ID” in TEJTE’s RF connector blog. A single photo comparison can save a full week of reordering delays.

What gain do you really need — 2 dBi, 3 dBi, or 6 dBi?

Antenna gain looks simple on paper, yet it’s one of the most misunderstood specs in the 2.4 GHz range. Higher gain doesn’t automatically mean better performance. What you’re really changing is pattern shape, not raw power.

- 2 dBi antennas radiate more evenly in all directions—perfect for short-range, indoor IoT nodes or mesh routers where coverage uniformity matters more than distance.

- 3 dBi models offer a sweet spot for general Wi-Fi and Bluetooth applications, balancing reach and vertical coverage.

- 6 dBi antennas focus the signal horizontally, which can double range in open areas but create “dead zones” directly above and below.

A quick mental rule:

“Length ≈ gain.”

At 2.4 GHz, a 2 dBi whip is roughly 3–5 cm; a 6 dBi version stretches closer to 20 cm. The longer element compresses the radiation lobe into a flatter donut, enhancing horizontal reach at the cost of vertical uniformity.

When picking for real deployments:

- Indoor mesh or smart-home: 2–3 dBi flexible rubber-duck or FPC antennas work best.

- Outdoor CPE or router: 5–6 dBi gives stronger point-to-point coverage, especially when both ends are elevated.

- Handheld IoT or sensors: stay near 2 dBi to minimize pattern distortion when users grip the device.

And remember—EIRP (Effective Isotropic Radiated Power) caps still apply. In the U.S., Wi-Fi systems can’t exceed FCC-limited EIRP values (typically 36 dBm for point-to-point). Using a high-gain antenna with a high-power transmitter may push you over that legal boundary, so always verify compliance.

Will cable length and type kill your 2.4 GHz link budget?

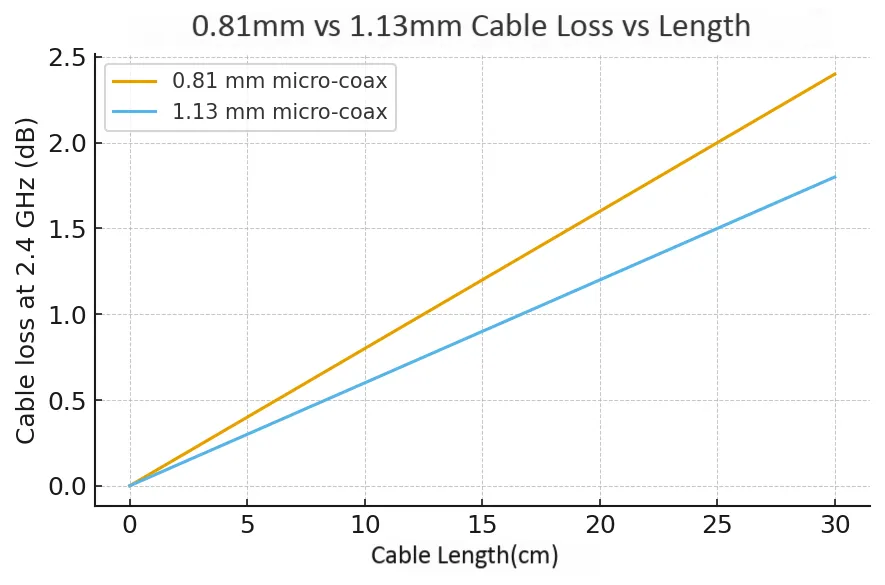

Figure redirects engineers’ attention from the antenna itself to the entire RF link. It reveals an often-overlooked fact: the “pipeline” connecting the antenna and the module itself has loss. Through data visualization, this image forces designers to think at the system level—a high-gain antenna can be undermined by a long or low-quality cable. It supports the document’s advice of “shorter is always better” and guides readers to choose lower-loss cable types (e.g., RG316) when longer runs are unavoidable.

At 2.4 GHz, the cable matters more than most people think. Every extra centimeter eats away at your signal strength. In practice, micro-coax losses can quickly cancel out the gains from a larger antenna.

A 0.81 mm coax loses roughly 0.8 dB per 10 cm, while 1.13 mm coax sits closer to 0.6 dB per 10 cm. Those differences seem small—until you have a 30 cm run. Add two connectors, and your 6 dBi antenna could be down to an effective 4.5 dBi.

Keep U.FL to SMA pigtails under 200–300 mm whenever possible. Beyond that, move the module closer to the antenna or use thicker cable.

EIRP = Tx power – cable loss – connector loss + antenna gain

If your EIRP drops below expectations, check pigtail length, crimp quality, and how many connector pairs sit in the chain. Even one poorly mated SMA joint can add 0.3 dB or more.

Shorter is always better. If you must go long, use RG316 or LMR-100, but note the tradeoff—less flexibility.

Can an omnidirectional antenna cover your use case better than a directional one?

Omnidirectional antennas are the default for most Wi-Fi and IoT systems. They create a 360° donut-shaped pattern, ideal for rooms or mesh networks. Yet “omni” doesn’t mean perfect uniformity—there’s always a null directly above and below the whip.

Directional antennas, like patch or Yagi, focus energy forward. A 9 dBi patch can outperform a 6 dBi omni if alignment is correct. Use them for outdoor or corridor links where direction is fixed.

| Use Case | Recommended Type | Typical Gain | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor Wi-Fi router / mesh | Omni whip / FPC | 2–3 dBi | Broad coverage; multipath tolerant |

| Outdoor CPE or bridge | Patch / Yagi | 6–9 dBi | Focused coverage; long distance |

| IoT sensors / handhelds | FPC / ceramic | 1–3 dBi | Compact; all-direction pattern |

| Access point clusters | Omni whip | 3–5 dBi | Avoids dead zones |

How to place internal Wi-Fi antennas in tight enclosures?

If your device uses an internal antenna, placement is everything.

The enclosure can amplify or destroy your signal depending on position.

Start with the keep-out zone: no ground planes, batteries, or screws within 10–15 mm of the antenna. Even a single metal bracket can detune resonance.

FPC antennas bend around corners or stick to plastic walls with adhesive. Ensure the active area faces outward, away from dense PCB regions.

PCB antennas need precise matching to ground cutouts and feedline impedance. If enclosure material changes, re-tune your network—dielectric variation shifts resonance.

Ceramic antennas are compact and predictable but narrowband. Follow layout specs—especially the ground clearance region.

During FCC pre-scan, rotate the device 90° each time.

If signal strength jumps drastically, your placement likely causes shadowing.

Do you need IPEX to SMA adapters—how do you choose the right chain?

Most IoT boards use IPEX (U.FL) connectors. To connect an external antenna, you’ll need a short pigtail and possibly a bulkhead SMA on the panel.

Each transition adds loss:

- U.FL connection ≈ 0.15 dB

- SMA connection ≈ 0.15 dB

Two pairs already mean nearly 0.6 dB.

Keep pigtails under 20 cm, secure them properly, and avoid frequent re-plugging (U.FL rated for ~30 cycles). Use sealing bulkheads for outdoor builds and a torque wrench (0.56–0.79 N·m) to avoid detuning.

Different vendors label U.FL equivalents as MHF4 / IPX4 / IPEX4, so check compatibility before ordering.

Order like a pro: what exact SKU attributes should be on the PO?

Once you’ve picked the right 2.4 GHz antenna, the final step is the purchase order.

A vague “SMA antenna, 3 dBi” line can stall your project for weeks.

Use this structured matrix to make every PO unambiguous.

| Category | Attribute & Parameter | Details / Options | Notes for Buyers & Engineers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connector & Gender | Type | SMA / RP-SMA / IPEX(U.FL) | Match connector family with module or router port |

| Gender | Male (pin) / Female (hole) | Mating mismatch is the #1 cause of reorders | |

| Thread | 7/16-28 UNF / M6 metric | Confirm for bulkhead feed-through types | |

| Antenna Specs | Gain (dBi) | 2 / 3 / 6 | Specify nominal gain—not marketing max |

| Length & Form | 5-20 cm; straight / right-angle / bendable | “Length ≈ gain” helps visualize pattern width | |

| Color | Black / White | White versions blend into indoor routers | |

| Cable Chain | Diameter | 0.81 / 1.13 mm / RG316 | Thicker cables reduce loss but add stiffness |

| Length | In cm (e.g., 20 cm) | Keep short (<30 cm) for minimal loss | |

| Interface to IPEX | U.FL to SMA / RP-SMA | Each pair adds ~0.15 dB loss | |

| Mounting | Style | Bulkhead / Adhesive / Inside-case | Match enclosure material |

| Environment & Compliance | Temp Range | -40 ~ +85 °C | Outdoor builds require full range |

| Certification | RoHS / REACH | Request vendor documentation | |

| Procurement Details | MOQ | e.g., 1 pcs | Check for sample quantities |

| Lead Time | 1-2 weeks typical | Buffer for logistics | |

It keeps engineering and purchasing perfectly aligned—and prevents the “wrong connector” crisis.

Part B — 2.4 GHz Antenna Ordering Matrix

Figure represents the “adapter” role in RF interconnects. In IoT devices, main boards are compact and often use IPEX connectors, while the enclosure interface requires more robust SMA connectors. The jumper cable shown in this image is the standardized solution to this矛盾. It reminds engineers that when ordering an antenna system, they must not only focus on the antenna itself but also clearly specify the attributes of these crucial adapter cables, such as length, cable type, and the gender/polarity of connectors on both ends, as each link affects overall performance.

| Category | Rubber-Duck Antenna | FPC Antenna | PCB Antenna | Ceramic Antenna |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connector Type | SMA / RP-SMA | IPEX (U.FL) | Solder Pad | IPEX (U.FL) |

| Gain (dBi) | 2 / 3 / 6 | 2 / 3 | 2 / 3 | 1 ~ 2 |

| Length / Form Factor | 5-20 cm · Straight / Right-Angle / Bendable | 50 × 12 mm adhesive flex | Integrated board trace | 8 × 2 mm chip |

| Color / Material | Black/White ABS | Yellow flex FPC | Green FR-4 | White ceramic |

| Cable & Length | RG316 / 1.13 mm (custom length) | 1.13 mm micro-coax | — | 0.81 mm micro-coax |

| Mounting Style | Bulkhead / Panel / Hinged | Inside-case | On-board | Inside-case adhesive |

| Operating Temp (°C) | -40 ~ +85 | -40 ~ +85 | -20 ~ +85 | -40 ~ +85 |

| Key Notes | RoHS/REACH · Fast lead time | Ideal for IoT modules | Cost-efficient | Compact narrowband for tight enclosures |

What’s new in 2.4 GHz for 2024–2025?

Wi-Fi 7 brings new 6 GHz channels but still relies on 2.4 GHz for legacy and IoT clients.

Matter and Thread protocols (also at 2.4 GHz) are expanding fast—driving the need for small, efficient antennas in smart devices.

Despite newer bands, 2.4 GHz remains the “reach band” for its wall penetration and low-power stability. Smart lighting, sensors, and controllers continue to depend on it.

Troubleshoot fast: why does the “stronger” antenna perform worse?

Swapping a 2 dBi whip for a 6 dBi and seeing worse results is common.

The reason? Multipath and over-gain.

Higher-gain antennas flatten their beam, which increases reflections in confined rooms, creating dead spots.

Some routers also auto-reduce power when detecting higher gain to stay within FCC limits.

Also, hand-grip detuning in portable devices can shift impedance and kill performance.

Debug smartly:

- Test with shorter cable.

- Swap connectors.

- Then change antenna.

Often, the “bad antenna” wasn’t bad—it was misused.

FAQ — your 2.4 GHz antenna questions, answered

Does higher gain always mean longer range indoors?

No. 6 dBi often causes vertical nulls. Stick to 2–3 dBi for apartments and offices.

How do I tell RP-SMA from SMA?

Look inside: pin = SMA-male; hole = RP-SMA-male. Reverse for females.

What’s the max safe U.FL → SMA length?

Keep under 200–300 mm; loss ≈ 0.6–0.8 dB/100 mm.

Can I mount FPC antennas on metal lids?

Only if separated by plastic adhesive or standoffs.

Why does my omni antenna have weak spots?

Omni covers 360° horizontally but not vertically—tilt slightly for balance.

Is 2.4 GHz still useful with Wi-Fi 7?

Yes. It’s unmatched for IoT and wall-penetrating reliability.

Do I need torque specs for SMA?

Yes—tighten to 0.56–0.79 N·m. Prevent detuning and damage.

Final Thoughts

Choosing the right 2.4 GHz antenna means balancing gain, cable loss, and placement—not just chasing numbers.

Keep pigtails short, double-check connector polarity, and always document every PO detail.

Whether you’re building a Wi-Fi 7 router or an IoT sensor, clarity up front saves hours later.

TEJTE supports custom SMA, RP-SMA, and IPEX antenna assemblies with consistent RF performance—because precision at 2.4 GHz starts long before your product hits the lab.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.