High Side Power Switch Design Guide for Modern 5 V & 12 V Rails

Nov 24,2025

Preface

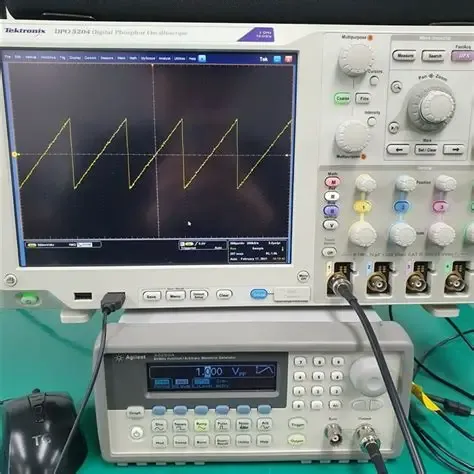

Figure is located in the article's preface, which mentions experience gained from benches, field deployments, and bring-up sessions. This figure specifically presents a key inspection phase in product development – an engineer using an oscilloscope to probe the performance of a high-side power switch board. This vividly reflects the document's core premise: theory must be validated by practice. By physically measuring key parameters like the switch's startup waveform and inrush current, its reliability in managing 5V or 12V rails in real applications is ensured, preventing unexpected dips or sparks and bringing the power rail's "personality" under control.

Anyone who has spent time around power rails knows they develop personalities of their own. Some wake up politely; others kick back the moment you hook them to real hardware. You can have a clean schematic, perfect simulations, and still get an unexpected dip or a spark when you finally bring the system to life. That’s usually when someone mutters, “Maybe a proper high-side switch would’ve saved us a headache.”

What follows isn’t theory dressed up as a whitepaper. It comes from benches, field deployments, and those late-night bring-up sessions where you realize the rail isn’t doing what you expected. A high side power switch exists to bring some order to that chaos, and the way load switch ICs wrap protections and timing into one block often makes a world of difference.

Introduction

Power rails behave strangely once they leave the safety of a schematic. A 5 V or 12 V supply might look rock-solid across a datasheet, but introduce real loads—an RF module with hefty input caps, a controller board with multiple regulators, or even a long cable—and the story changes fast. You might see a sudden sag, a noisy startup, or a reset that shouldn’t have happened. A high side power switch gives you a way to shape these moments instead of reacting to them.

Integrated load switch ICs take it a step further. Instead of juggling MOSFETs, RC timing, and improvised gate control, you get predictable ramps, UVLO, thermal protection, and an honest PGOOD signal. In RF modules and mixed-rail embedded systems, that predictability is gold; it keeps one rail from stumbling into another.

This guide keeps the conversation practical: what tends to fail, how rails behave in the real world, and why a structured checklist helps before you commit to copper. When the NCP45560 shows up later, it’s simply used as a familiar reference—its behavior lines up neatly with the rail considerations most engineers already track.

Why does a high side power switch matter on 5 V and 12 V rails?

It only takes a single hot-plug event or a long harness to remind you how unpredictable rails can be. A steady 5 V or 12 V line might suddenly dip when it hits downstream capacitance, or it may surge hard enough to make connectors sparkle. Without a high side power switch, the supply pours current straight into the load and hopes for the best. Sometimes it works; sometimes it takes half the system down with it.

A controlled switch slows all of this down. It lets you decide how quickly the rail rises, how much inrush is acceptable, and how faults should be handled. In systems where digital logic, analog blocks, and RF circuits live side by side, that level of control keeps startup from turning into a chain reaction of resets or odd behavior.

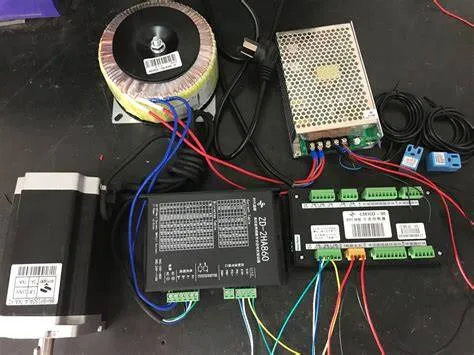

Map real loads to your power rails

The context for Figure emphasizes the importance of "mapping real loads to your power rails." This figure visually demonstrates this process: an evaluation board integrating a high-side load switch IC has its output connected simultaneously to an RF module and a small motor. The RF module represents loads with large input capacitors and potential high inrush current during startup, while the motor represents inductive loads whose current can multiply during startup or stall. This parallel connection demonstrates the multiple challenges the switch faces in a real system, highlighting the necessity of selecting and protecting the power switch based on the dynamic characteristics of the loads, not just their static specifications.

Real loads rarely behave like the tidy numbers printed in their specs. An RF front-end might sip a few hundred milliamps once running, yet yank several amps while charging its input capacitors. That same pattern appears in MCU carrier boards with multiple regulators and protection devices—they start politely only after they’ve had their initial gulp of current.

Move to 12 V rails and everything becomes more dramatic. Small fans, pumps, and motors can draw several times their rated current during startup or stall. Recognizing those behaviors early tells you whether a simple gate is enough or if you need the predictability of a high side load switch with built-in protections.

Identify common failure modes without a controlled load switch

Skipping a controlled switch introduces a series of issues most engineers eventually run into:

- a tiny spark when someone hot-plugs a connector

- inrush so high it briefly drags the rail down

- resets that appear “random” until you trace them back to startup

- connectors wearing out faster than they should

- dips on one rail disturbing another

These problems don’t always show up in early prototypes. They wait until the system is inside an enclosure, wired through longer harnesses, or paired with bulkier downstream caps. Smoothing the ramp with a load switch IC avoids much of this drama.

When is “just a MOSFET” no longer enough?

A discrete MOSFET looks tempting—cheap, familiar, quick to drop onto a board. But once you start adding RC networks for gate shaping, comparators for UVLO, and some form of current limiting, it stops being simple. At that point you’ve nearly rebuilt what an integrated load switch IC already provides: predictable slew, thermal shutdown, current limiting, reverse blocking, and cleaner sequencing.

When you need a rail to behave the same way across units, temperatures, and product revisions, that consistency matters more than shaving a few cents off the BOM.

Sketch a 12 V rail example for fans, pumps or small motors

The context for Figure describes an application: a microcontroller manages a small pump via a high-side power switch. When firmware asserts EN, the pump's initial surge is limited by the controlled ramp, preventing a sudden step load on the upstream 12V converter. This controlled startup and built-in current limiting benefit thermal stability in sealed enclosures and protect against stall conditions.

A 12 V rail tends to behave differently from its 5 V counterpart, especially when it feeds mechanical loads. Fans, pumps, and compact motors often draw only a fraction of an amp once spinning, yet their startup pulse can be three to five times that. Suppose a microcontroller manages a small pump through a high side power switch like the one used previously. When firmware asserts EN, the pump’s initial surge tries to pull the rail down. With a controlled ramp, the switch limits that first gulp so the upstream 12 V converter isn’t hit with a sudden step load.

If the system sits inside a sealed enclosure—as many IoT or sensor units do—the reduced surge helps stabilize thermal behavior. Motors that occasionally stall also benefit from built-in current limiting; instead of repeatedly slamming the supply, the load switch IC constrains the current until the fault clears or firmware intervenes. The PGOOD output can even help sequence dependent logic, ensuring downstream monitoring circuits see a stable rail before performing measurements. This keeps the 12 V domain predictable whether the motor is lightly loaded, cold, or starting again after a brief stall.

Control inrush current and soft start without overcomplicating the circuit

Designers often underestimate how much inrush shapes overall power integrity. A rail may behave fine on the bench, yet once field wiring, larger-than-expected capacitors, or stacked modules enter the picture, the startup waveform becomes far less friendly. A high side load switch gives you a way to slow things down just enough to avoid tripping upstream supplies or introducing jitter into nearby analog paths.

The goal isn’t to “perfectly engineer” the ramp—it’s to make it slow enough that the supply and downstream load move together instead of fighting each other. Many load switch ICs expose internal slew-rate control or soft-start mechanisms so you don’t need to hand-tune RC networks. When combined with current limiting, these features keep the rail’s behavior stable across temperature, cable variations, and product revisions without turning the design into a science project.

Estimate inrush energy and why “slow enough” is sometimes safer than “fast”

Inrush isn’t just about peak current; it’s also about how much energy the rail dumps into downstream capacitance in a short window. The familiar I = C × dV/dt equation reminds you that ramp rate pulls the strings. A fast rise charges caps quickly, and those caps answer by drawing large instantaneous current. If the ramp is slowed slightly, the inrush drops dramatically with almost no functional downside.

In many RF systems or sensor hubs, a rushed startup causes more trouble than a deliberately paced one. A too-sharp dV/dt can disturb upstream converters or inject noise into sensitive front-ends. Letting the high side power switch manage the slope keeps the rail well-behaved, and in many cases “slow enough” ends up being the safest—and simplest—choice.

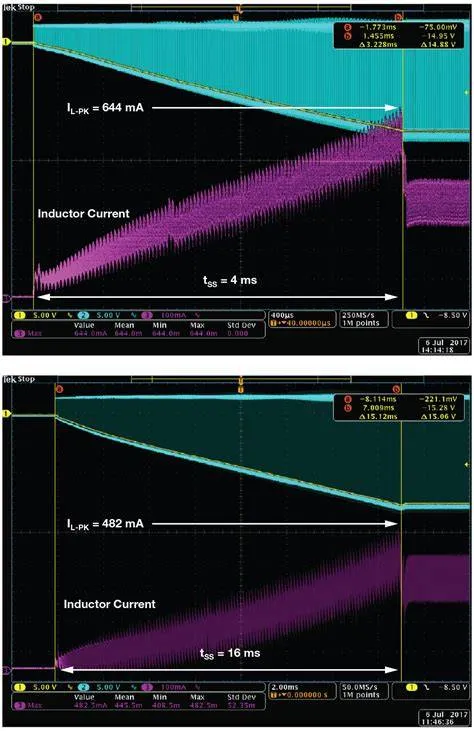

Use slew rate control inside a high side power switch IC

The context corresponding to Figure emphasizes the importance of slew rate control. When a load switch IC shapes the internal gate rise, the output follows a clean, predictable slope. This helps upstream converters struggling with current jumps and sensitive analog circuitry. Internal slew control also behaves consistently across temperature/tolerance, unlike external RC networks.

Slew rate control is one of those features that looks minor in the datasheet but makes a big difference on the bench. When a load switch IC shapes how fast the gate rises internally, the output rail follows a clean, predictable slope rather than a harsh step. That’s especially helpful when the upstream converter struggles with sudden current jumps or when analog circuitry nearby dislikes abrupt transitions.

Internal slew control also behaves the same across temperature and component tolerance—something external RC networks rarely manage. One board revision may work flawlessly, while another drifts just enough to cause startup jitter. Letting the high side power switch manage the slope avoids those inconsistencies. Even a slight slowdown in the rise can protect upstream rails from overshoot and keep sensitive loads from reacting unpredictably.

When you still need an external inrush current limiter IC

Not every rail can be tamed with an integrated switch alone. Some systems use large banks of capacitors—LED arrays, long cable harnesses, or industrial sensors that sit meters away from the control board. In those cases, even a well-behaved high side load switch may struggle to keep the surge within bounds.

External limiters step in when the energy behind the inrush simply exceeds what a soft-start slope can absorb. They spread the charging over a longer period or clamp the current to a safe level regardless of downstream behavior. This is common in automotive, HVAC, or remote-sensor installations where cable capacitance isn’t fully predictable. When the rail needs more than just a slowed ramp, pairing a switch with a dedicated limiter keeps fault energy from startling the upstream supply.

Monitor power good signal and power rail sequencing in real projects

Once the rail’s behavior is under control, the next challenge is timing. Many systems—RF front-ends, mixed-signal microcontroller domains, or sensor modules—expect their rails to appear in a particular order. If one wakes up before its companion, the module may latch in an odd state or misreport data. A high side power switch with a PGOOD pin simplifies sequencing by clearly signaling when the rail is ready.

Sequencing doesn’t need a full-blown controller. In many designs, PGOOD from one rail directly drives EN for the next. This daisy-chain approach keeps dependencies aligned without extra logic. Field diagnostics also benefit: firmware can log transitions in PGOOD to help spot rails that rise too slow, reach threshold inconsistently, or unexpectedly drop while the system is running. These logs become invaluable when debugging hardware installed in remote or enclosed environments.

How to interpret a power good signal from a load switch IC

PGOOD often looks like a simple digital pin, but it’s more of a quiet status line that tells you how the rail is behaving underneath. On most load switch ICs, PGOOD asserts only after the output voltage crosses a defined threshold—usually tied to a percentage of VIN—and stays stable long enough to ensure the downstream device won’t start in a half-powered state.

In practice, you don’t treat PGOOD as an exact voltage reference. Instead, you read it as “the rail is genuinely usable now.” It avoids the timing uncertainty that comes from polling ADCs or watching the raw voltage through noisy startup transitions. Whether you’re powering an RF module, a microcontroller domain, or a small 12 V motor driver, that clean handshake ensures initialization routines don’t fire too early—one of the more common causes of unpredictable behavior during bring-up.

Use high side power switches to implement simple power rail sequencing

Rail sequencing doesn’t always require a dedicated controller. Many designers simply chain PGOOD from one switch to the EN pin of the next. Because a high side power switch already shapes ramp behavior and reports stability, it naturally becomes part of a lightweight sequencing chain.

For example, a system might need its 3.3 V logic to come up before the 5 V RF bias rail. Linking the two with PGOOD→EN ensures the RF path doesn’t see voltage until the logic domain is truly alive. This avoids partial-power conditions that leave PLLs, ADCs, or digital interfaces misaligned. Sequencing can also prevent sudden current stacking—if multiple rails rise at once, their combined inrush can overwhelm the upstream converter. Staggering them helps avoid that.

Logging PGOOD events for field diagnostics and reliability

Once a system ships, most debugging becomes remote debugging. Logging PGOOD transitions offers a surprisingly effective window into rail health without extra sensors. If a rail flickers, rises slower than expected, or drops during operation, the firmware can timestamp these events and flag them for later review.

Systems installed in sealed housings—industrial sensors, remote gateways, RF test nodes—benefit even more. A drifting upstream converter or a failing cable harness often shows up first as irregular PGOOD activity. Feeding those logs into maintenance routines allows technicians to spot failing rails long before they become hard faults. When paired with a high side load switch, this creates a lightweight form of power-integrity monitoring without needing full telemetry hardware.

What recent high side power switch IC developments should you know about?

New load switch ICs with ideal diode and reverse blocking functions

One noticeable shift is the appearance of switches that merge load gating with ideal-diode behavior. These load switch ICs handle forward conduction efficiently while blocking unwanted reverse current—useful in systems where multiple rails or backup sources may momentarily overlap. Reverse blocking used to be handled with discrete diodes or FET arrangements, but integrated ideal-diode control avoids losses and keeps the transfer smooth.

This is particularly relevant in portable or modular equipment. When different boards can be hot-swapped or powered from alternate inputs, preventing backfeed becomes critical. By combining controlled slew with robust reverse isolation, these switches give designers fine-grained authority over when and how power moves through the system—something a plain MOSFET rarely achieves without additional circuitry.

Smart automotive high side switches and diagnostics trends

Automotive electronics continue pushing the boundary. Smart high-side switches in this space integrate current sensing, fault reporting, programmable limits, and thermal modeling. Instead of just reacting to faults, they help detect wiring degradation, intermittent shorts, or abnormal startup profiles. For vehicles and industrial machinery, this context is invaluable; it lets a control unit understand why a load misbehaved, not merely that it tripped.

Although these parts sit outside the “simple consumer load switch” category, the underlying logic is the same: tighter control and clearer feedback. What used to require an external shunt, an amplifier, and a microcontroller now fits into a compact power distribution switch IC. This trend continues to influence smaller embedded designs, where space and serviceability matter just as much.

Market outlook: why load switch ICs are growing in IoT and edge devices

IoT devices, wearables, and distributed sensor nodes all share a similar challenge: limited space, unpredictable loads, and the need for rails that don’t interfere with each other. As these systems scale, designers increasingly rely on high side load switch devices to segment domains, isolate peripherals, and manage power states without requiring bulky controllers.

Another factor is deployment environment. Once a system is mounted on a pole, shoved into a wall cavity, or sealed in a weatherproof box, debugging becomes difficult. Consistent power sequencing and built-in protection reduce field failures dramatically. This reliability is part of the reason load switches see growing adoption across edge computing and compact RF devices. As more designs move toward modularity and low standby power, these ICs become less optional and more of a foundational building block.

Troubleshoot high side power switch failures in the lab

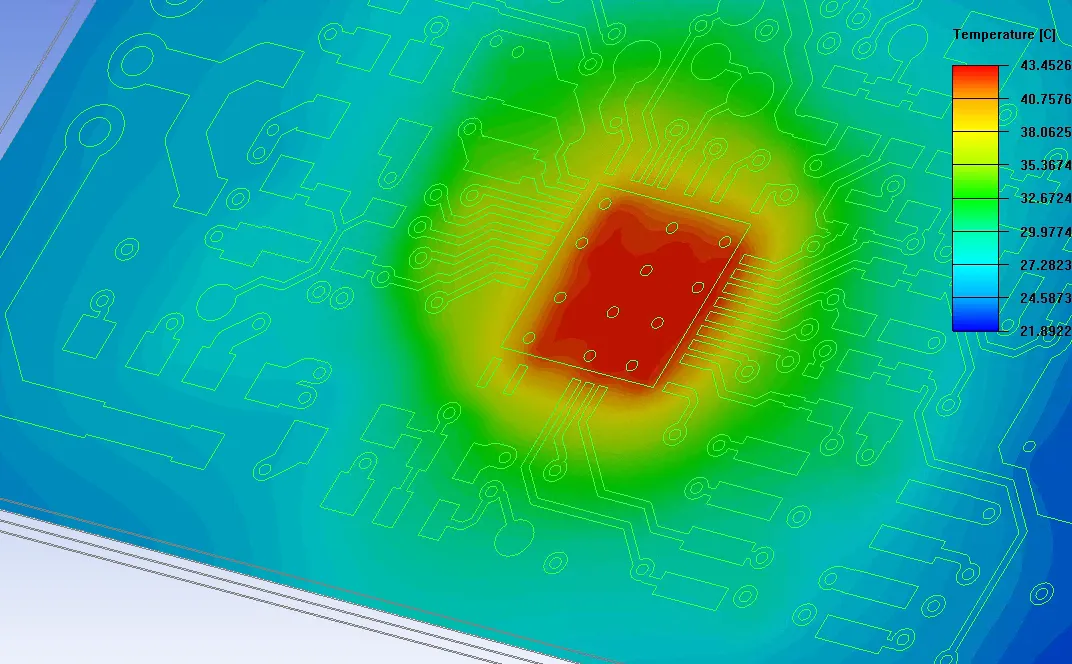

Recognize symptoms of mis-sized RDS(on) or thermal issues

Figure is located in the "Troubleshoot" section, illustrating how to recognize failures due to mis-sized RDS(on) or thermal issues. The context states that a rail sagging after minutes points to thermal buildup. If the RDS(on) is too high, the device dissipates excess heat. A thermal camera reveals hot spots. The fix is usually choosing a lower RDS(on) device or improving PCB heatsinking.

Debug false trips from UVLO or short-circuit protection

Check layout, ground return and sense lines before blaming the IC

It’s tempting to assume the IC is at fault, but layout mistakes cause a surprising number of switching problems. A long ground return can introduce enough impedance to distort protection thresholds. Routing EN or PGOOD alongside noisy digital traces may cause the switch to toggle unintentionally. Likewise, a narrow copper pour on the output path can heat up and mimic an overloaded rail.

Before replacing the device, walk through the layout with fresh eyes: short, direct ground paths; clean power routing; and minimal coupling between sensitive pins and high-slew nets. A power distribution switch IC behaves best when the PCB gives it a solid electrical foundation.

Answer common high side power switch design questions

Can a high side power switch replace a relay in low-voltage designs?

How is a load switch IC different from using a discrete MOSFET?

When should I choose a smart high side switch instead of an eFuse?

How do I size a high side power switch for capacitive loads?

Do I always need a power good signal and rail sequencing?

What layout mistakes kill high side power switches the fastest?

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.