SMA Extension Cable: Length, Loss & Bulkhead Tips

Nov 21,2025

Preface

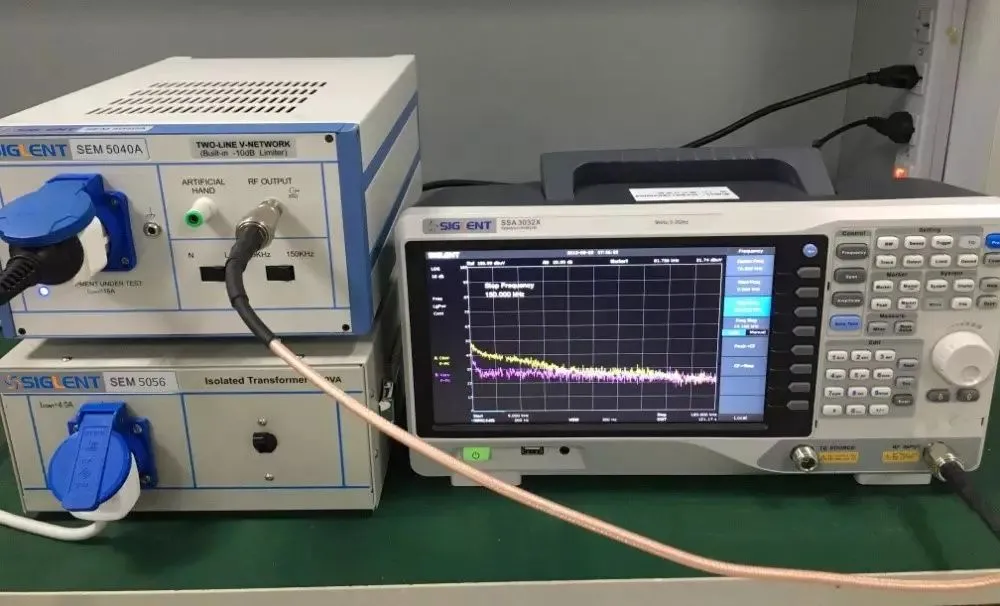

This image illustrates the physical characteristics of RG316 cable, emphasizing its slim profile, flexibility, and brown FEP jacket. It highlights how the cable maintains predictable performance even under stress, such as when squeezed or bent in crowded bench setups.

Choosing an SMA extension cable sounds trivial until you see how much it can influence a 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi link, a 5 GHz test setup, or a GNSS front-end with only a few dB of link margin. A run that’s a little too long—or a connector pair added without thinking—can quietly erode SNR, stretch return-loss budgets, and even push small test modules into thermal derating.

In TEJTE’s lab, we see this often. A customer extends a module’s SMA port using a 2 m jumper, loops it twice around a bracket, and then wonders why their RSSI drops 4–5 dB. Or a technician uses two adapters instead of one clean extension, creating three extra interfaces. None of these are “mistakes” in the classical sense—they’re normal shortcuts—but in higher-frequency work, every interface has a cost.

This guide organizes the decision-making process the way engineers actually approach it: start with the shortest workable length, budget insertion loss with real attenuation numbers, check bend radius against the cable’s OD, map connector genders correctly, and only then consider bulkhead or feedthrough choices. The goal is simple: a cleaner, more predictable 50-Ω chain that behaves the same tomorrow as it does today.

Throughout the article, real data from RG316 and RG316D assemblies is used, along with TEJTE SMA connector parameters such as VSWR ≤1.10–1.15, insertion loss ≤0.15 dB @ 6 GHz, and mechanical durability ≥500 cycles. These numbers give practical context to each recommendation rather than hand-waving estimates.

Your dataset reinforces this point with real figures instead of vague claims. The cable’s attenuation curve—0.29 dB/m at 100 MHz, 0.93 dB/m at 1 GHz, 1.46 dB/m at 2.4 GHz, and 2.34 dB/m at 6 GHz—lines up with what engineers see on analyzers every day. The mechanical numbers are just as important: 15 mm minimum bend radius for RG316, 13 mm for RG316D, tensile strength around 3.4 kg, and jacket temperatures ranging from 150 °C to 255 °C depending on construction. These constraints shape how long a jumper should be, how tight its routing can get, and how many cycles it truly survives.

With those real parameters as the baseline, the next few sections walk through the practical decisions engineers make when sizing, bending, and loss-budgeting rg316 coax—decisions that research papers rarely capture but every lab technician knows well.

How do you decide the right length for an SMA extension cable?

Figure serves as the introductory image for its section, emphasizing the decision that engineers revisit most often - length selection. Once installed, the cable becomes part of the long-term RF baseline, making the initial length decision critical.

The length decision is the one engineers revisit the most, and for good reason: once the extension is installed in the field or inside an enclosure, it’s rarely touched again. That means the cable becomes part of the long-term RF baseline, not just a temporary jumper.

A simple rule holds across nearly every application—from Wi-Fi 6E and lab instruments to embedded GNSS modules: use the shortest length that does not require looping, sharp bending, or strain on either connector. Looped cable doesn’t just look untidy; it changes how the braid sits, increases micro-bending loss, and may induce mechanical stress where the dielectric meets the pin. We’ve measured cases where a 1 m run looped twice behaves closer to 1.1–1.15 m due to these effects.

Preset ranges that work in practice

Many engineers default to familiar lengths because they keep systems predictable:

- 0.1–0.3 m for inside-enclosure jumpers

- 0.5–0.6 m for bench setups where DUTs move occasionally

- 1.0–2.0 m for antenna-to-router paths (only when necessary)

Short SMA pigtails—for example, 15–30 cm RG316 leads—are particularly common for RF modules that must sit close to a chassis wall. A short, factory-terminated jumper is almost always cleaner than a pair of adapters.

When a single extension beats two adapters

A frequent lab shortcut is chaining: SMA-male-to-female into another male-to-female so a test head can reach a DUT. Functionally it works, but electrically it adds:

- 2 extra interfaces

- 20–30 mm of unsupported length

- A small but measurable RL impact

TEJTE’s connectors consistently achieve VSWR ≤1.10–1.15 (straight), yet stacking them compounds mismatch. Replacing adapters with a single SMA extension cable reduces the interface count, improves stability, and makes it easier to maintain consistent torque.

There’s also strain relief to consider. Two back-to-back SMA barrels or gender-changers create a rigid mid-section prone to twisting. A short RG316 or RG316D jumper absorbs this movement without stressing the DUT port.

How much insertion loss should you budget at 900 MHz / 2.4 GHz / 5 GHz?

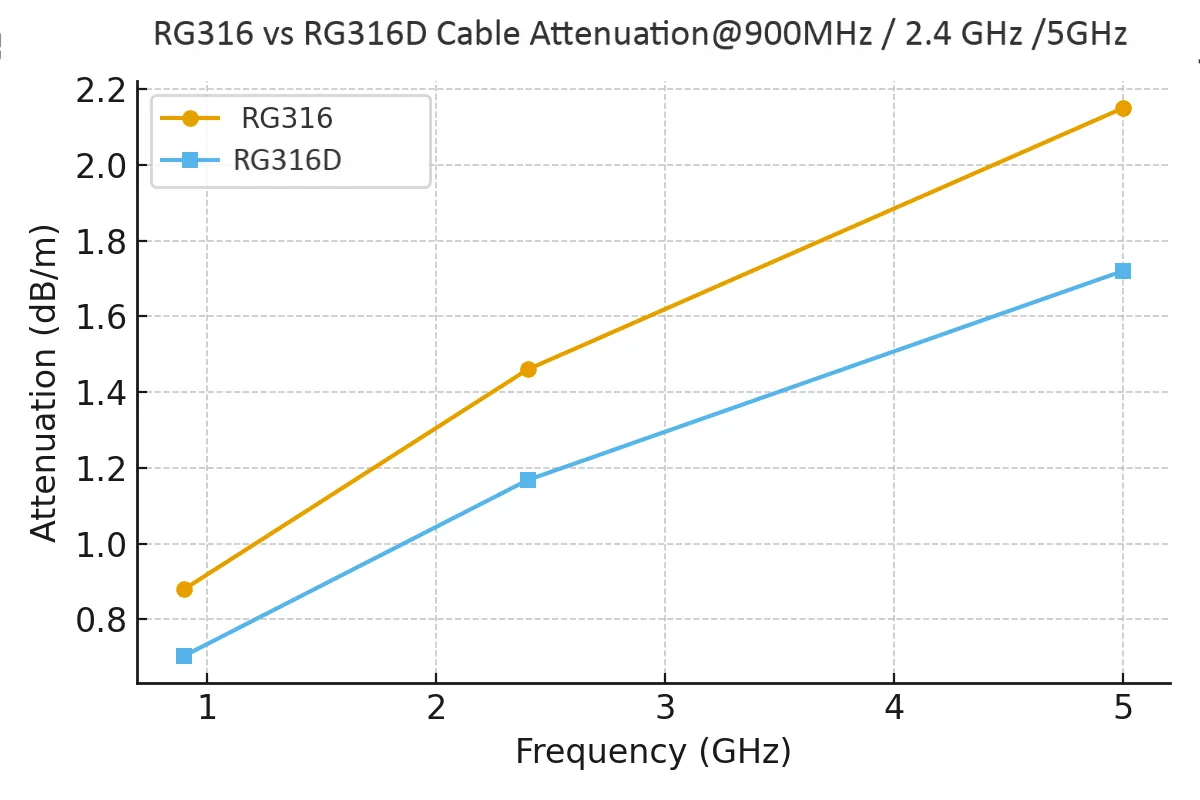

Insertion loss is where theory meets reality. Cable vendors often quote a handful of frequencies, but budgeting across 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, and 5 GHz covers the bulk of modern applications—sub-GHz ISM, Wi-Fi, IoT, GNSS L-band, and 5 GHz test paths.

Thanks to the complete attenuation tables you provided, we can use actual, verifiable numbers instead of generic industry values.

Real RG316 attenuation (25 °C, sea level)

Figure is closely related to the table of real RG316 attenuation data at 900MHz/2.4GHz/5GHz. It visually displays the layers that make up the RG316 cable: silver-plated copper inner conductor, PTFE dielectric, silver-plated copper braid, and FEP jacket. This structure explains how its stable dielectric properties and tight braiding work together to achieve predictable high-frequency attenuation performance.

| Frequency | Loss (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| 900 MHz | 0.88 |

| 2.4 GHz | 1.46 |

| 5 GHz | 2.15 |

These align well with TEJTE’s RG316 construction:

- Ag-plated Cu inner conductor (7 × 0.175 mm)

- PTFE dielectric (Ø 1.53 mm)

- Silver-plated copper braid

- FEP jacket, OD 2.50 mm

The structure explains the performance: a stable dielectric, tight braiding, and silver plating keep high-frequency attenuation predictable.

Real RG316D attenuation (double-shielded)

| Frequency | Loss (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| 900 MHz | ~0.72 |

| 2.4 GHz | ~1.55 |

| 5 GHz | ~2.55 |

Connector & interface penalties

Figure illustrates TEJTE's straight SMA connector. According to the context, this connector achieves a VSWR of ≤1.10–1.15 up to 6 GHz and an insertion loss of ≤0.15 dB at 6 GHz. It represents a high-performance, low-loss straight interface option and serves as the benchmark for building clean RF chains.

- Straight SMA (SMA-J-1.5)

- VSWR ≤1.10–1.15 up to 6 GHz

- IL ≤0.15 dB @ 6 GHz

Figure illustrates TEJTE's right-angle SMA connector. The text indicates that, compared to straight connectors, the right-angle version introduces a predictable penalty: VSWR increases to 1.20–1.30, with an extra loss of approximately 0.05–0.12 dB. However, it is often mechanically superior by relieving torque and strain in cramped spaces, thereby improving connection reliability.

- Right-angle SMA (SMA-JW-1.5)

- VSWR ≤1.20–1.30

- Extra loss ≈ 0.05–0.12 dB

These real numbers will be embedded into the calculator below.

- Right-angle SMA (SMA-JW-1.5)

SMA Extension Cable Loss & Fit Calculator

Input Fields

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| frequency_MHz | 100-6000 |

| length_m | 0.1-3.0 |

| cable_type | RG316 / RG316D |

| OD_mm | 2.5 (RG316) / 3.0 (RG316D) |

| interfaces_count | 2-6 |

| IL_if_dB | 0.05-0.20 |

| VSWR | 1.10-1.35 |

| ambient_temp_°C | -20 to +85 |

| min_bend_rule | ×OD (default: 10×) |

| need_bulkhead | Y/N |

| need_RA | Y/N |

Output Fields

| Output | How it's calculated |

|---|---|

| cable_loss_dB | α × length |

| interface_loss_dB | IL_if_dB × interfaces |

| mismatch_loss_dB | -10·log₁₀(1-ρ²), ρ=(VSWR-1)/(VSWR+1) |

| IL_total_dB | Sum of all losses |

| ReturnLoss_dB | 20·log₁₀((VSWR+1)/(VSWR-1)) |

| BendCheck | PASS/FAIL vs 10×OD |

| PowerDerateFactor | (1 - (T-25)/ΔT_max) / VSWR |

Example Output (real numbers)

(1.0 m RG316 @ 2.4 GHz, 2 interfaces, VSWR 1.15)

- cable_loss_dB ≈ 1.46

- interface_loss_dB ≈ 0.10

- mismatch_loss_dB ≈ 0.03

- Total ≈ 1.59 dB

This is consistent with what TEJTE sees in Wi-Fi 6E benches and embedded device testing.

What bend-radius & jacket rules keep the assembly reliable?

Engineers often assume an SMA extension cable fails because of the connector. In reality, most long-term degradation starts in the cable body—especially in tight enclosures where the jumper must turn immediately after the boot. With RG316 and RG316D, the way the dielectric and braid respond to stress plays a bigger role than many expect.

TEJTE’s RG316 specifications list a minimum bend radius of 15 mm, while RG316D, despite being slightly thicker, allows 13 mm thanks to its tighter dual-braid structure. These values aren’t safety margins—they represent the point where PTFE begins to distort and the inner conductor strands stop distributing strain evenly.

Short rule: treat bends within 10×OD as the “critical zone”

For RG316 (OD ≈ 2.5 mm), this means 25 mm.

For RG316D (OD ≈ 3.0 mm), 30 mm.

Bending tighter than this near the connector boot causes localized deformation that can lead to slow increases in IL or shifts in phase stability. In vibration-heavy environments—industrial cabinets, moving fixtures, or field equipment—the effect compounds.

How jacket material affects durability

Both cables use FEP jackets, which behave predictably across wide temperatures. RG316 is rated to 150°C, while RG316D operates from –55°C to +255°C. FEP recovers well after flexing, resists abrasion, and holds its shape when routed around metal edges.

The difference lies in shielding. RG316D’s double braid improves:

- EMI rejection

- mechanical roundness under compression

- VSWR consistency across flex cycles

If your enclosure has several RF modules, high-current converters, or digital backplanes, double shielding typically pays off. The braided structure also anchors the dielectric more firmly, giving RG316D better long-term stability.

For deeper construction context, see the RG316 coax guide—it outlines how braid coverage, dielectric uniformity, and jacket hardness relate directly to bending behavior.

How do you map SMA male to SMA female directions without mistakes?

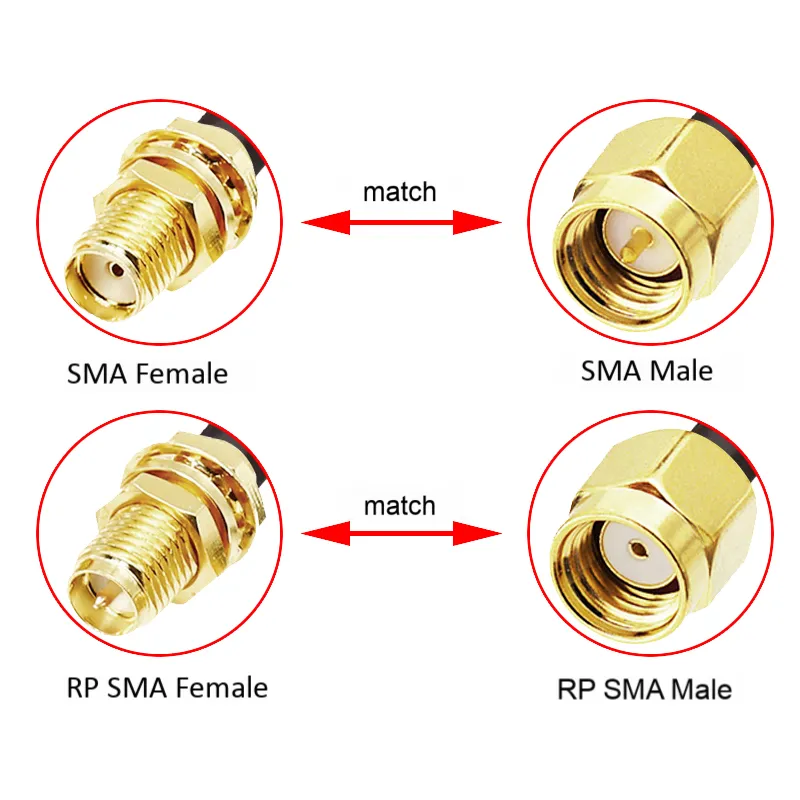

Figure is located in the section "How do you map SMA male to SMA female directions without mistakes?". It provides a visual comparison to clearly distinguish the gender definitions for standard SMA and Reverse Polarity (RP-SMA). The document emphasizes that mapping mistakes often happen because people look at the threads instead of the inner contact. This figure serves as key guidance to prevent the use of extra adapters due to gender mismatches, which adds interfaces and degrades return loss.

Even experienced engineers sometimes misidentify SMA genders when switching between straight, bulkhead, and right-angle parts. It happens because people look at the threads, not the contact.

The rule remains simple:

- SMA male to inner pin

- SMA female to inner sleeve

This holds true even on bulkhead versions where the threaded body might look misleading.

Why mapping mistakes happen

In enclosure builds, a board may have an SMA female jack, but the technician sees the external thread and assumes they need a female extension. The result? A last-minute search for adapters, extra interfaces, and avoidable insertion loss.

A similar problem happens when mixing SMA and RP-SMA. RP-SMA keeps the same thread pattern but swaps the gender of the inner conductor—easy to miss unless you look closely

Straight vs right-angle SMA ends

TEJTE straight connectors like SMA-J-1.5 achieve:

- VSWR ≤1.10–1.15 (0–6 GHz)

- Insertion loss ≤0.15 dB @ 6 GHz

Right-angle versions such as SMA-JW-1.5 introduce a predictable penalty:

- VSWR up to 1.20–1.30

- IL increase of 0.05–0.12 dB

Despite the penalty, a right-angle plug often improves reliability by relieving torque. When a cable exits sideways out of a cramped chassis, the strain on the module port is significantly reduced.

Labeling source to load

One method used widely in our lab is simple but effective:

- Identify the source port (module, VCO, test head).

- Identify the load port (antenna, analyzer, router).

- Confirm the extension cable orientation: male to female in the right direction.

This avoids last-minute gender changers, which add two interfaces and degrade return loss. The SMA to BNC adapter article explains a similar mapping challenge when mixing connector families.

Do you need a bulkhead or feedthrough at the enclosure wall?

Bulkhead connectors sit at the crossroads of electrical and mechanical design. They determine grounding quality, sealing, torque resistance, and long-term stability. TEJTE’s SMA bulkhead options—including open-end styles and standard SMA-K-7 types—maintain:

- 0–6 GHz frequency range

- VSWR ≤1.15 (straight)

- Insertion loss ≤0.15 dB @ 6 GHz

- 500-cycle durability

- Thread lengths of 7 mm / 8.5 mm / 10 mm / 13 mm for different panel thicknesses

- Insulation resistance ≥5000 MΩ

These parameters define how well the connector transitions RF energy through the enclosure wall.

Panel thickness and washer stack-up

A bulkhead must:

- compress the flat + lock washer correctly,

- seat the shoulder flush against the panel,

- maintain ground continuity across the enclosure.

Thread that’s too short prevents proper tightening.

Thread that’s too long causes wobble and side-loads the internal cable.

Grounding & sealing

Bulkhead + short jumper vs direct pass-through

Bulkhead + short RG316 jumper (most common)

- Offloads torque from the PCB-mounted SMA.

- Handles movement inside the enclosure.

- Simplifies repair and replacement.

Direct cable pass-through

Works when:

- the enclosure is thin,

- environmental sealing isn’t required,

- the internal module is rigidly mounted.

Outdoor systems often use an N-type bulkhead externally paired with an SMA jumper internally. The robustness of N-type threads helps avoid mechanical failures, as discussed in the N-type bulkhead connectors overview.

In mixed-connector setups, you may also reference your SMA cable assemblies for mapping male-to-female signal paths inside the housing while keeping loss low.

Will power handling or VSWR limit your application?

Where length and insertion loss decide overall signal quality, power handling determines whether the cable survives thermal stress over time. RG316 and RG316D both use silver-plated copper conductors and PTFE dielectric—materials with predictable RF heating characteristics—but their ratings differ.

According to your data, RG316 supports up to 78 W at 2.4 GHz and roughly 61 W at 5 GHz under continuous-wave conditions at 25°C. RG316D, with its double braid and slightly thicker diameter, generally runs slightly cooler at the same current density, though power ratings scale similarly with frequency.

De-rating with temperature

A simple way to think about power handling is to consider how the dielectric dissipates heat relative to ambient. PTFE behaves consistently until temperatures rise well above 100°C, but once the environment exceeds 50–60°C—with nearby power electronics, enclosed housings, or sunlight exposure—thermal rise adds up.

A practical engineering estimate works like this:

PowerDerateFactor ≈ (1 − (ambient_temp − 25) / ΔT_max) / VSWR

If your ambient is 55°C and ΔT_max is ~100°C for PTFE-based assemblies, you’re already trimming ~30% off your continuous rating. And that’s before factoring in mismatch.

VSWR-driven heating

Mismatch creates standing waves, and those waves concentrate energy in specific regions of the cable. With TEJTE connectors achieving straight SMA VSWR ≤1.10–1.15 and right-angle SMA ≤1.20–1.30, your worst-case mismatch loss remains small—but at 5 GHz even a slight mismatch generates non-trivial heating over long runs.

A quick rule of thumb:

If VSWR exceeds 1.35, avoid continuous high-power signals unless the cable length is short and well-cooled.

Are power limits a concern in low-power systems?

For typical Wi-Fi, GNSS, LoRa, BLE, and test-module setups, cable heating is rarely the bottleneck. Most systems operate at 0–2 W. The real concern is that high VSWR shortens RF front-end life, especially in PA-driven radios.

In short:

- For low-power digital radios to VSWR is the bigger risk.

- For lab sources and power amplifiers to both VSWR and temperature matter.

What recent RF news should influence extension-length choices?

Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be) certification

5G-Advanced (3GPP Release 18)

VNAs up to 54 GHz in mid-range categories

The trend toward higher-frequency bench instruments makes interface quality more important. While RG316 and RG316D are not intended for 54 GHz operation, their connector quality and interface count matter even at moderate frequencies. A poor transition at 5 GHz won’t catastrophically fail at 10 GHz, but it can distort calibration planes, especially when working near noise floors.

Taken together, modern RF trends reinforce a familiar message:

shorter paths and fewer interfaces deliver more predictable results.

How do you order an exact SKU with zero back-and-forth?

Poorly specified orders lead to delays more often than technical issues. SMA extension cables are mechanically simple, yet a missing attribute—gender, jacket color, connector orientation—can trigger multiple emails.

A clean configuration includes:

1. Length

2. Connector genders

SMA-male to SMA-female is the most common.

Specify direction clearly (e.g., male at source, female at load).

3. Orientation

Straight to Right-angle.

Right-angle ends especially need clarification on which side they mount to in mechanical layouts.

4. Bulkhead requirement

If a bulkhead is needed:

- state thread length (7 / 8.5 / 10 / 13 mm),

- include panel thickness,

- clarify washer stack (flat / lock washer).

5. Cable type

- RG316 (OD 2.5 mm, 150°C)

- RG316D (OD 3.0 mm, 255°C)

6. Additional documents

Many engineers request:

- RoHS / REACH statements

- Serialization (for test tracking)

- Torque notes for SMA mating

Providing this upfront prevents second-round emails and aligns expectations between purchasing and engineering.

FAQs

How long can an SMA extension be from antenna to router?

How do I connect an SMA RF cable to a wireless access point?

Which cable families pair well with SMA connectors?

Is a right-angle SMA plug worse than a straight one?

How do I attach an SMA or RP-SMA connector to a cable?

What’s a good Wi-Fi SMA cable today?

Will power handling limit my application?

Closing Notes

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.